The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume III October 1894

Contents

Literature

I. Women — Wives or Mothers By A Woman . . Page 11

II. “Tell Me Not Now” William Watson . . 19

III.

The Headswoman . . Kenneth

Grahame . . 25

IV. Credo . . . . Arthur Symons . . 48

V. White

Magic . . . Ella D’Arcy . . . 59

VI. Fleurs de Feu . José Maria de

Hérédia, of the French Academy . 69

VII. Flowers of Fire, a Translation Ellen M. Clerke . . 70

VIII.

When I am King . . Henry

Harland . . 71

IX. To a Bunch of Lilac .

Theo Marzials . . 87

X. Apple-Blossom in Brittany Ernest Dowson . . 93

XI.

To Salome at St. James’s Theodore Wratislaw . 110

XII. Second Thoughts . . Arthur

Moore . . 112

XIII. Twilight . . . Olive Custance . . 134

XIV. Tobacco Clouds . . Lionel Johnson . . 143

XV.

Reiselust . . . Annie

Macdonell . . 153

XVI. To Every Man a Damsel

or Two C.S. . . . . 155

XVII. A Song and a Tale . . Nora

Hopper . . . 158

XVIII. De Profundis . .

. S. Cornish Watkins . 167

XIX. A Study in Sentimentality Hubert Crackanthorpe . 175

XX. George Meredith . . Morton

Fullerton . . 210

XXI. Jeanne-Marie . .

Leila Macdonald . . 215

XXII. Parson Herrick’s Muse . C.W.

Dalmon . . 241

XXIII. A Note on George the

Fourth Max Beerbohm . . 247

XXIV.

The Ballad of a Nun . John

Davidson . . 273

Art

The Yellow Book—Vol. III.—October, 1894

Art

Front Cover, by Aubrey Beardsley

Title Page, by Aubrey Beardsley

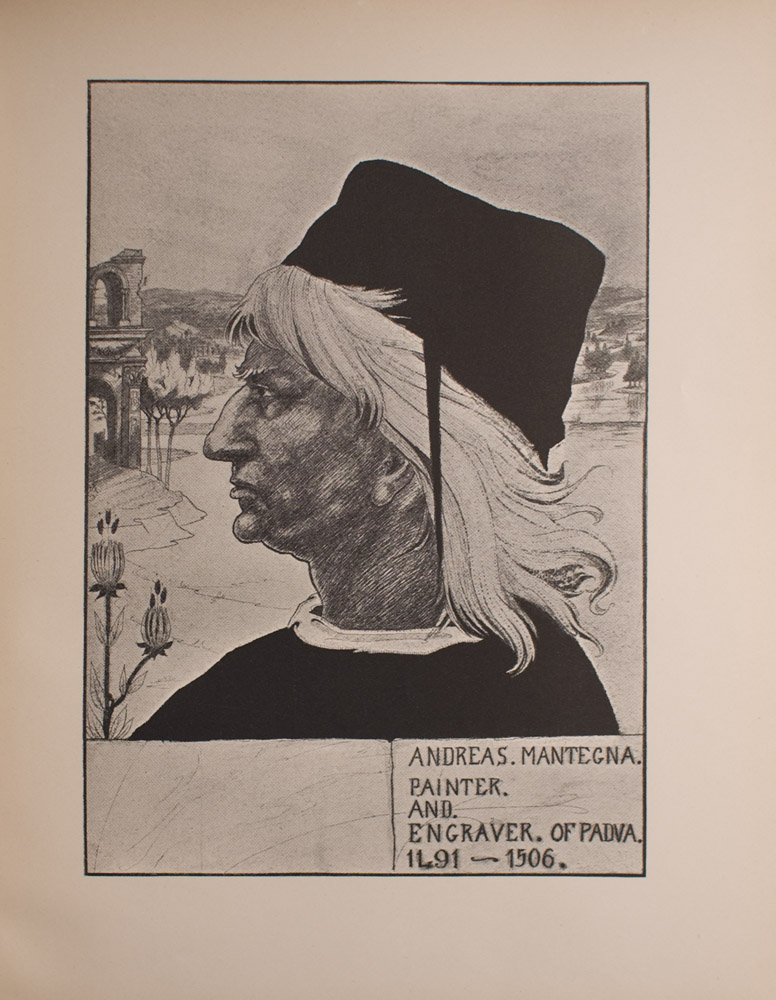

I. Mantegna . . . By Philip

Broughton . Page 7

II. From a Lithograph . . George Thomson

. . 21

III. Portrait of Himself . Aubrey Beardsley . . 50

IV.

Lady Gold’s Escort

V. The Wagnerites .

VI. La

Dame aux Camélias

VII. From a Pastel . . Albert

Foschter . . 89

VIII. Collins’ Music Hall,

Islington Walter Sickert

. . 136

IX. The Lion Comique

X. Charley’s Aunt .

XI. The Mirror . .P. Wilson Steer . . 169

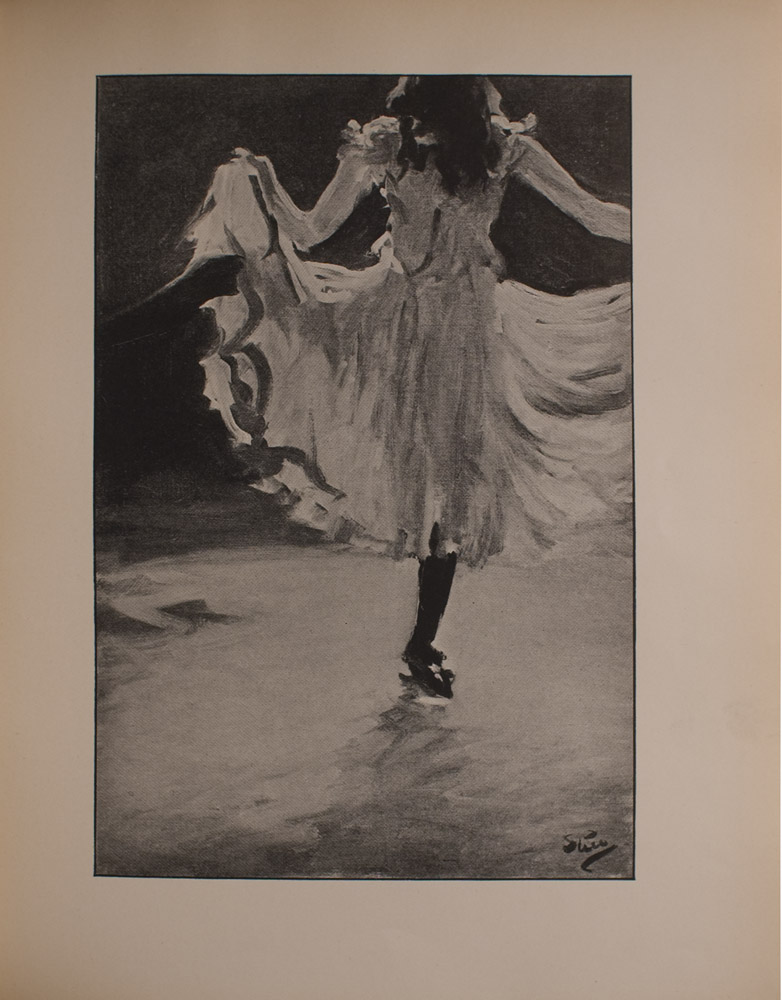

XII.

Skirt-Dancing .

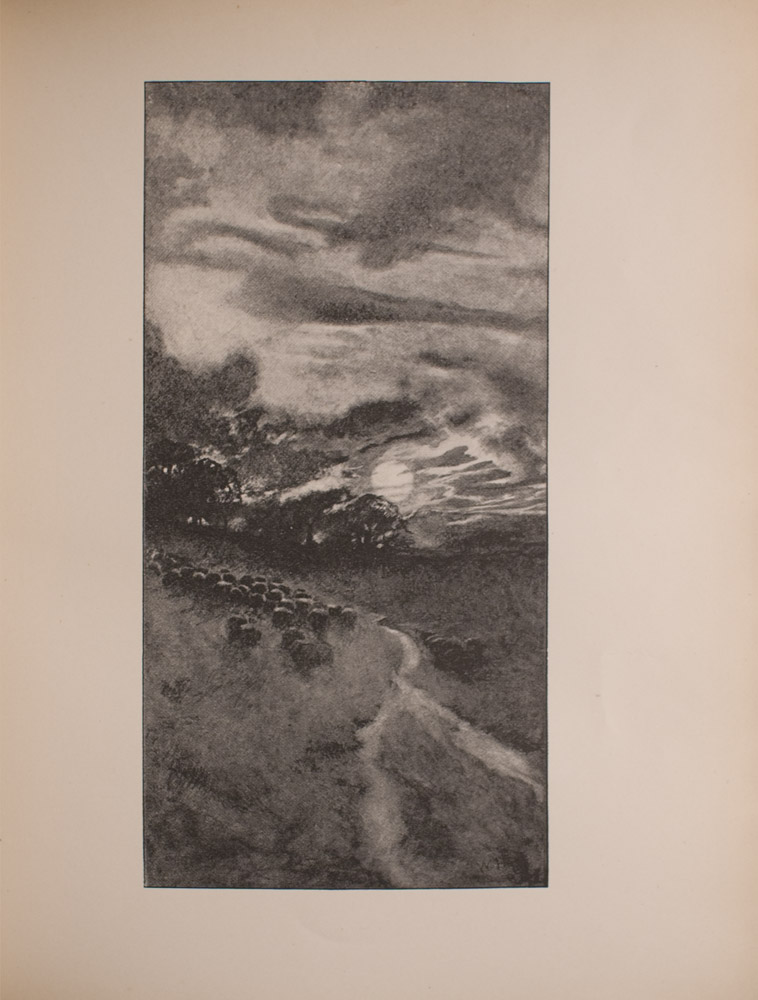

XII. A Sunset . . . William Hyde . . 211

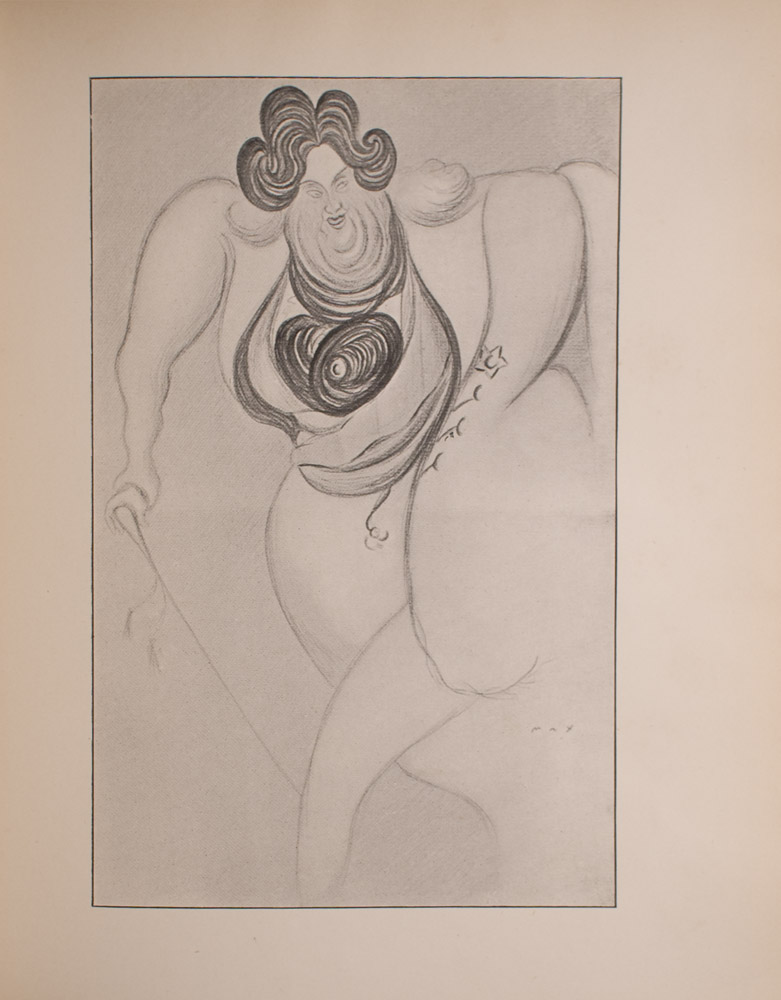

XIV.

George the Fourth . . Max

Beerbohm . . 243

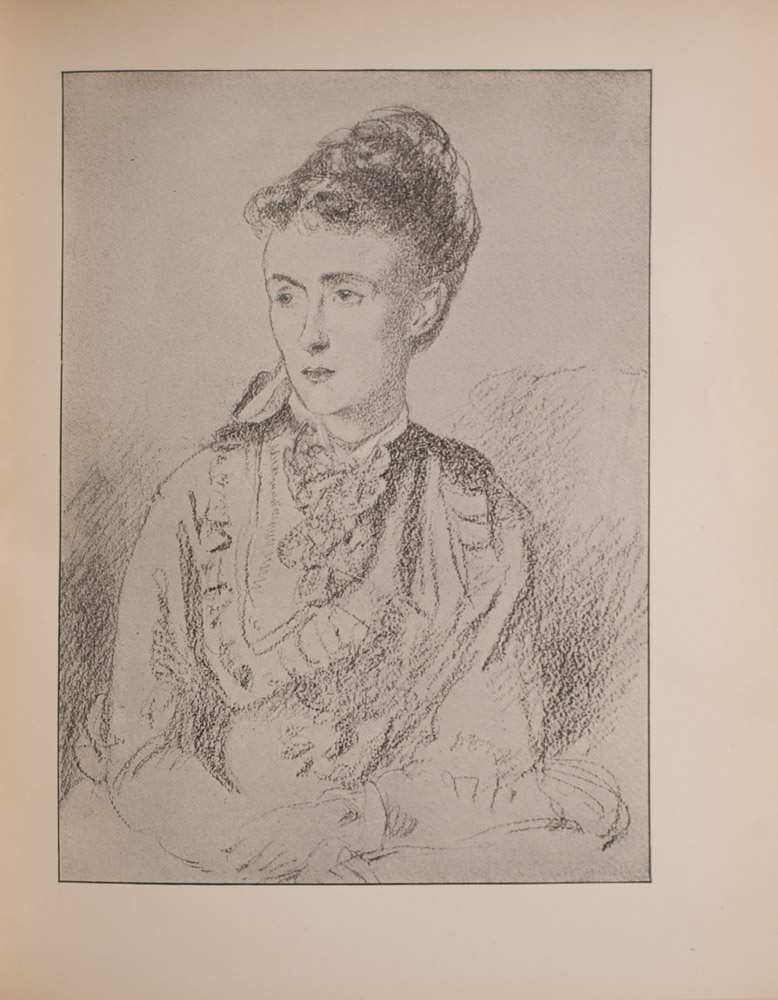

XV. Study of a Head .

. An Unknown Artist . 270

Back Cover, by Aubrey Beardsley

Advertisements

Women—Wives or Mothers

By a Woman

WE believe it to be well within the truth to say that most

men cherish, hidden

away in an inner pocket of conscious-

ness, their own particular ideal of the

perfect woman. Sole

sovereign she of that unseen kingdom, and crowned and

sceptred

she remains long after her faithful subject has put aside the

other

playthings of his youth. The fetish is from time to time regarded

rapturously, though sorrowfully, by its possessor, but it is never

brought forth

for public exhibition. If to worship and adore

were the beginning and end of the

pastime, no cavilling word

need be said, for the power to worship is a great and

good gift,

and, save in the fabulous region of politics, is nowadays so rare

an

one, that when discovered in the actual world its steady encour-

agement

becomes a duty. But to this apparently innocent diver-

sion there is another

side. Somewhat grave consequences are apt

to follow, and it is to this point of

view that we wish to call

attention.

When the woman uncreate becomes the measuring rod by which

her unconscious

living rivals are judged, and are mostly found

wanting, then we are minded to

lift up our voice and put in

a plea for fair-play. To the shrined deity are

given by the acolo-

thyst, not only all the perfections of person demanded by a

severely

aesthetic

aesthetic sense, but all the moral qualities as well. Every grace of

every fair

woman he has ever met—the best attributes of his

mother, his sister, and his

aunt—are freely hers. None of the

slight blemishes which occasionally tarnish

the high lustre of

virtue, none of the caprices to which sirens are

constitutionally

liable, are permitted. Faultless wife and faultless mother must

she

be, faithful lover and long-suffering friend, or he will have none

of

her in his temple. Now, this is surely a wholly unreasonable,

an utterly

extravagant demand on the part of man, and if analysed

carefully, will, we

believe, be found to yield egoism and gluttony

in about equal parts. How, we

venture to inquire, would he meet

a like claim, were it in turn presented to him

? A witty and light-

hearted lady—a remnant yet remains, in spite of the advent

of the

leaping, bounding, new womanhood—once startled a selected

audience

by the general statement, “All men are widowers.”

But even if this generous

utterance can be accepted as absolutely

accurate, it can hardly be taken as a

proof of man’s fitness for

both the important roles involved.

For our own part, we are convinced that, broadly speaking,

the exception only

proving the rule—whatever that supporting

phrase may mean—woman, fresh from

Nature’s moulding, is, so far

as first intention is concerned, a predestined

wife or mother. She

is not both, though doubtless by

constant endeavour, art and duty

taking it turn and turn about, the dual end

may, with hardness, be

attained unto. For Nature is not economic. Far from her

is

the fatal utilitarian spirit which too often prompts the improver

man

(or—dare we confess it ?—still more frequently woman) to

attempt to make one

object do the work of two. From all such

sorry makeshifts Nature, the great

modeller in clay, turns contemp-

tuously away. Not long ago we read in a lady’s

journal of a

‘combination gown’ which by some cunning arrangement, the

secret

secret whereof was only known to its lucky possessor, would do

alternate day and

night duty with equal credit and despatch. We

have no desire to disparage the

varied merits of this ingenious con-

trivance, but at the best it must remain an

unlovely hybrid thing.

Probably it knew this well, for gowns, too, have their

feelings, and

before now have been seen to go limp in a twinkling, overcome

by a sudden access of despondency. Such a moment must certainly

have come to the

omnibus garment referred to above, when it

found itself breakfasting with a

severe and one-idea’d “tailor-made,”

or, more cruel experience still, dining

skirt by skirt with a

“mysterious miracle”—the latest label—in gossamer and

satin.

We dare to go even further, and to declare that every woman

knows in her

heart—though never, never will she admit it to you—

within which fold she was

intended to pass. Is it an exaggeration

to say that many a girl marries out of

the superabundance of the

maternal instinct, though she may the while be

absolutely ignorant

of the motive power at work ? Believing herself to be

wildly

enamoured of the man of her (or her parents’) choice, she is in

reality only in love with the nursery of an after-day. Of worship

between

husband and wife, as a factor in the transaction, she

knows nothing, or likely

enough she imagines it present when it

is the sweet passion of pity, or the more

subtle patronage of

bestowal, one or both, which are urging her forward into

marriage.

Gratitude, none the less real because unrealised, towards the man

who thus enables her to fulfil her true destiny—the saving of souls

alive—has

also its share in the complex energy. Well for the

husband of this wife if he

allows himself gradually to occupy the

position of eldest and most important of

her children, to whom

indeed a somewhat larger liberty is accorded, but from

whom also

more is required. In return for this submission boundless will be

the care and devotion bestowed upon his upbringing day by day.

He

He will be foolish if he utters aloud, or even says in the silence of

his heart,

that motherhood is good, but that wifehood was what he

wanted. It would be but a

bootless kicking against the pricks.

For he has chosen the mother-woman, and it

is beyond his

power, or that of any other specialist, to effect the

fundamental

change for which his soul may long. It only remains for him to

make the best of a very good bargain, and one to which it is very

probable his

strict personal merits may hardly have entitled him.

If such a marriage is childless, it may still be a very useful one.

Nature’s

accommodations often verge on the miraculous. The

unemployed maternal instincts

of the wife easily work themselves

out in an unlimited and universal auntdom. It

must be confessed

that bad blunders are apt to ensue, but where the intentions

are

good, the pavement should not be too closely scanned. In fiction

these

are the Dinahs, the Romolas, the Dorotheas, the Mary

Garths. Dear to the soul of

the female writer is the maternal

type. With loving, if tiresome frequency, she

is presented to us

again and yet again. In truth we sometimes grow a little

weary

of her saintly monotony. But as it is given to few of us to have

the

courage of our tastes, we bear with her, as we bear with other

not altogether

pleasing appliances, presented to us by earnest

friends, with the assurance that

they are for our good, or for our

education, or some other equally superfluous

purpose.

With the male artist this female model is not nearly so popular.

It may be that

he feels himself wholly unequal to cope with her

countless perfections. Certain

it is that he makes but a sad

muddle of it when he tries. Witness Thackeray’s

faded, bloodless

Lady Esmond, as set against his glowing wayward Trix—she,

by the way, a beautifully-marked specimen of the wife-woman—

though whether it

would be pure wisdom to take her to wife

must be left an open question. Still,

we have in our time loved

her

her well, and some of us have found it hard to forgive the black

treachery done

in bringing her back in her old age, a painted

and scolding harridan. For these,

well-loved of the gods, should, in

fiction at least, die young.

Truth compels us to own regretfully that man in his self-indul-

gence shrinks

from both the giving and receiving of dull moments,

whilst woman, believing

devoutly in their saving grace, is altruistic

enough to devote herself with

enthusiasm to the task of their ad-

ministration. Now, dull moments are apt to

lie hidden about the

creases of the severely classic robe, which, in the

story-books at

any rate, these heroines always wear. We must all agree that

during the last twenty years this type, with its portentous accumu-

lation of

self-conscious responsibility has increased alarmingly.

To what is the increase

to be attributed ? The too rapid growth

of the female population stands out

plainly as prime cause. Legis-

lators are athirst for things practical. Is it

beyond their power to

devise some method of dealing with this problem ? The

Chinese

plan is painfully obvious, but only as a last and despairful

resource,

when the wise men of Westminster sitting on committees and

commissions have failed, can it be mentioned for adoption in

Europe. We are,

alas ! Science-ridden, and are likely to remain

thus bridled and saddled for

weary years to come. Every bush

and every bug grows its own specialist, and yet

we, the patient,

the long-suffering public, are left to endure both the fogs

that

make of London one murky pit, and the redundant female birth-

rate

which threatens more revolutions than all the forces of the

Anarchists in active

combination. Meanwhile these devotees of

the abstract play about with all sorts

of trifles, masquerading as

grave thinkers, hoping thus to escape their certain

judgment-day.

The identification of criminals by the variation of

thumb-prints

is a pretty conceit ; so too is the record of the influence of

the

moon

moon on the tides, which, we are informed, employs all to itself a

whole and

highly paid professor with a yearly average of three

pupils at Cambridge. But

what are these save mere fads, on a par

with leapfrog and skittles, in the

presence of the momentous

problems about and around us ? Let these gentlemen

jockeys look

to it. The hour is not far distant when public opinion shall

discover their uselessness and send them about their business.

In humbler ways, too, much might be done to stem the morbid

activity of the

collective female conscience. Big sins lie at the

doors of the hosts of good men

and women who turn out year by

year tons of “books for the young” to serve as

nutriment for the

hungry nestlings of culpable, thoughtless parents. It is hard

to

overstate the pernicious effect of this class of motif literature.

Féerie in old or new dress is the only nourishing food for

the

happy child who is to remain happy. The little girl, aged seven,

who

lately wrote in her diary before going to bed, “Of what real

use am I in the world ?” had, it is certain, been denied her

Andersen, her

Grimm, her Carroll, even her Blue fairy book.

Turned in to browse on ”

Ministering Children,” “Agatha’s First

Prayer,” and the fatal “Eric”—into how

many editions has this

last well-meaning but poisonous romance not passed—the

little

victim of parental stupidity is thus left with an organ damaged for

life by over-much stimulation at the start. This new massacre of

the innocents

is of purely nineteenth-century growth. It dates

from the era of the awakened

conscience, and is coincident

with the formation of all the societies for the

regeneration of the

human race.

Per contra, the wife-woman, though but seldom to be

met

with in the multitudinous pages written by women, is the well-

beloved,

the chosen of the male artist. Week-days and Sundays

he paints her portrait.

Shakespeare returns to her again and again,

as

as though it were hard to part from her. Wicked Trix stands out

as bold leader

of one bad band. Tess belongs to the family, though

she is of another branch ;

so does Cathy of Wuthering Heights,

and Lyndall of the African Farm ; whilst

latest and slightest scamp

of the lot comes dancing Dodo of Lambeth. Save in a

strictly

specialised sense, none of this class can be said to contrive the

greatest good of the greatest number. These are the women to

whom the nursery is

at best but an interlude, and at worst a real

interruption of their life’s

strongest interests. They are not

skilled in dealing with early teething

troubles, nor in the rival

merits of Welsh and Saxony flannel stuffs. Their

crass ignorance

of all this deep lore may, it is true, go far to kill off

superfluous

offspring, but, unjust as it would appear, these are the

mothers

who each succeeding year become more and more adored of their

sons.

Fribblers though they be, they sweeten the world’s corners

with the perfume of

their charm. And the bit of world’s work in

which they excel is the keeping

alive the tradition of woman’s

witchery. Who, then, can deny them their plain

uses ? When

Fate is kind and bestows the fitting partner, the fires of their

love

never die down. They remain lovers to the end. Their husbands

need

fear no rival, not even in the person of their own superior

son. When Fate is

unkind and things go crookedly, these are the

women whose wreckage strews life’s

high road, and from whom

their wiser sisters turn reprovingly away. For the good

woman

who has to “work for her living,” and who pretends to enjoy the

healthful after-pains in her moral system, is rarely tolerant of the

existence

of the leichtsinriige sister for whom, as to Elijah at

the

brook, dainty morsels without labour are cheerfully provided by

that

inconsequent raven, man. This lady goes gaily, wearing

what she has not spun,

reaping where she has not sown. Sad

reflections these for the high-souled woman

whose enlightened

demand

demand for justice turns in its present day impotency to wrath and

bitterness.

Wisdom and foresight are never the “attributes of the wife-

woman. Charm,

beguilement, fascination of sorts, form her poor

equipment for life’s selective

struggle. These gifts cannot be said

to promise, save when the stars are in

happiest conjunction, long

life and useful days for her intimates. Variations of

the two types

of Primitive Woman may abound, but the broad distinction

between them is clearly cut and readily to be made out by

the dullest groper

after truth. We can imagine a modern Daniel

addressing (quite uselessly) a modem

disciple thus :

“Look to it now, O young man ! that your feet go straight, and

slip not in

search for the pearl that may be hid away for you.

For she who loveth you best

may work you all evil, and she who

loveth her own soul’s travail best will

hardly fail you in the days

and the years. But Love remaineth, and the way of

return

is not.”

“Tell me not Now”

By William Watson

TELL me not now, if love for love

Thou canst return,

Now while around us and above

Day’s flambeaux burn.

Not in clear noon, with speech as clear,

Thy heart avow,

For every gossip wind to hear ;

Tell me not now !

Tell me not now the tidings sweet,

The news divine ;

A little longer at thy feet

Leave me to pine.

I would not have the gadding bird

Hear from his bough ;

Nay, though I famish for a word,

Tell me not now !

The Yellow Book—Vol. III. B

But

But when deep trances of delight

All Nature seal ;

When round the world the arms of Night

Caressing steal ;

When rose to dreaming rose says, “Dear,

Dearest ;” and when

Heaven sighs her secret in Earth’s ear,

Ah, tell me then !

The Headswoman

I

IT was a bland sunny morning of a mediaeval May—an old-style

May of

the most typical quality ; and the Council of the little

town of

St. Radegonde were assembled, as was their wont at that

hour, in

the picturesque upper chamber of the Hotel de Ville, for

the

dispatch of the usual municipal business. Though the date was

early sixteenth century, the members of this particular town-

council possessed some resemblance to those of similar assemblies

in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and even the nineteenth

centuries,

in a general absence of any characteristic at

all—unless a pervading

hopeless insignificance can be considered

as such. All the character,

indeed, in the room seemed to be

concentrated in the girl who

stood before the table, erect, yet

at her ease, facing the members in

general and Mr. Mayor in

particular ; a delicate-handed, handsome

girl of some eighteen

summers, whose tall, supple figure was well set

off by the quiet,

though tasteful mourning in which she was clad.

“Well, gentlemen,” the Mayor was saying ; “this little business

appears to be—er—quite in order, and it only remains for me

to—

er—review the facts. You are aware that the town has lately

had

the misfortune to lose its executioner—a gentleman who, I

may

say,

say, performed the duties of his office with neatness and dispatch,

and gave the fullest satisfaction to all with whom he—er—came in

contact. But the Council has already, in a vote of condolence,

expressed its sense of the—er—striking qualities of the deceased.

You are doubtless also aware that the office is hereditary, being

secured to a particular family in this town, so long as any one of

its

members is ready and willing to take it up. The deed lies

before

me, and appears to be—er—quite in order. It is true that

on this

occasion the Council might have been called upon to

consider and

examine the title of the claimant, the late lamented

official having

only left a daughter—she who now stands before

you ; but I am

happy to say that Jeanne—the young lady in

question—with what

I am bound to call great good-feeling on her

part, has saved us all

trouble in that respect, by formally

applying for the family post,

with all its—er—duties, privileges,

and emoluments ; and her

application appears to be—er—quite in

order. There is therefore,

under the circumstances, nothing left

for us to do but to declare

the said applicant duly elected. I

would wish, however, before I—

er—sit down, to make it quite clear

to the—er—fair petitioner,

that if a laudable desire to save the

Council trouble in the matter

has led her to a—er—hasty

conclusion, it is quite open to her to

reconsider her position.

Should she determine not to press her

claim, the succession to

the post would then apparently devolve

upon her cousin

Enguerrand, well known to you all as a practising

advocate in the

courts of this town. Though the youth has not,

I admit, up to now

proved a conspicuous success in the profession

he has chosen,

still there is no reason why a bad lawyer should

not make an

excellent executioner ; and in view of the close friend-

ship—may

I even say attachment ?—existing between the cousins,

it is

possible that this young lady may, in due course, practically

enjoy the solid emoluments of the position without the necessity

of

of discharging its (to some girls) uncongenial duties. And so,

though not the rose herself, she would still be—er—near the

rose

!” And the Mayor resumed his seat, chuckling over his little

pleasantry, which the keener wits of the Council proceeded to

explain at length to the more obtuse.

“Permit me, Mr. Mayor,” said the girl, quietly, “first to thank

you

for what was evidently the outcome of a kindly though mis-

directed feeling on your part ; and then to set you right as to

the

grounds of my application for the post to which you admit

my

hereditary claim. As to my cousin, your conjecture as to

the

feeling between us is greatly exaggerated ; and I may further

say

at once, from my knowledge of his character, that he is

little quali-

fied either to adorn or to dignify an important

position such as this.

A man who has achieved such indifferent

success in a minor and

less exacting walk of life, is hardly

likely to shine in an occupation

demanding punctuality,

concentration, judgment—all the qualities,

in fine, that go to

make a good business man. But this is beside

the question. My

motives, gentlemen, in demanding what is my

due, are simple and

(I trust) honest, and I desire that you should

know them. It is

my wish to be dependent on no one. I am

both willing and able to

work, and I only ask for what is the

common right of

humanity—admission to the labour market.

How many poor toiling

women would simply jump at a chance

like this which fortune lays

open to me ! And shall I, from any

false deference to that

conventional voice which proclaims this

thing as “nice,” and that

thing as “not nice,” reject a handicraft

which promises me both

artistic satisfaction and a competence ?

No, gentlemen ; my claim

is a small one—only a fair day’s wage

for a fair day’s work. But

I can accept nothing less, nor consent

to forgo my rights, even

or any contingent remainder of possible

cousinly favour !”

There

There was a touch of scorn in her fine contralto voice as she

finished speaking ; the Mayor himself beamed approval. He was

not

wealthy, and had a large family of daughters ; so Jeanne’s

sentiments seemed to him entirely right and laudable.

“Well, gentlemen,” he began, briskly, “then all we’ve got to

do, is

to——”

“Beg pardon, your worship,” put in Master Robinet, the

tanner, who

had been sitting with a petrified, Bill-the-Lizard sort

of

expression during the speechifying ; “but are we to understand

as

how this here young lady is going to be the public

executioner

?”

“Really, neighbour Robinet,” said the Mayor somewhat

pettishly,

“you’ve got ears like the rest of us, I suppose ; and

you know

the contents of the deed ; and you ve had my assurance

that

it’s—er—quite in order ; and as it’s getting towards lunch-

time——”

“But it’s unheard-of,” protested honest Robinet. “There

hasn’t ever

been no such thing—leastways not as I’ve heard

tell.”

“Well, well, well,” said the Mayor, “everything must have a

beginning, I suppose. Times are different now, you know.

There’s

the march of intellect, and—er—all that sort of thing.

We must

advance with the times—don’t you see, Robinet ?—

advance with the

times !”

“Well I’m——” began the tanner.

But no one heard, on this occasion, the tanner’s opinion as to

his

condition, physical or spiritual ; for the clear contralto cut

short his obtestations.

“If there’s really nothing more to be said, Mr. Mayor,” she

remarked, “I need not trespass longer on your valuable time. I

propose to take up the duties of my office to-morrow morning, at

the

the usual hour. The salary will, I assume, be reckoned from the

same

date ; and I shall make the customary quarterly application

for

such additional emoluments as may have accrued to me during

that

period. You see I am familiar with the routine. Good

morning,

gentlemen !” And as she passed from the Council

chamber, her

small head held erect, even the tanner felt that she

took with

her a large portion of the May sunshine which was

condescending

that morning to gild their deliberations.

II

One evening, a few weeks later, Jeanne was taking a stroll on

the

ramparts of the town, a favourite and customary walk of hers

when

business cares were over. The pleasant expanse of country

that

lay spread beneath her—the rich sunset, the gleaming sinuous

river, and the noble old château that dominated both town and

pasture from its adjacent height—all served to stir and bring out

in her those poetic impulses which had lain dormant during the

working day ; while the cool evening breeze smoothed out and

obliterated any little jars or worries which might have ensued

during the practice of a profession in which she was still

something

of a novice. This evening she felt fairly happy and

content.

True, business was rather brisk, and her days had been

fully

occupied ; but this mattered little so long as her modest

efforts

were appreciated, and she was now really beginning to

feel that,

with practice, her work was creditably and

artistically done. In

a satisfied, somewhat dreamy mood, she was

drinking in the

various sweet influences of the evening, when she

perceived her

cousin approaching.

“Good

“Good evening, Enguerrand,” cried Jeanne pleasantly ; she

was

thinking that since she had begun to work for her living, she

had

hardly seen him—and they used to be such good friends.

Could

anything have occurred to offend him ?

Enguerrand drew near somewhat moodily, but could not help

relaxing

his expression at sight of her fair young face, set in its

framework of rich brown hair, wherein the sunset seemed to have

tangled itself and to cling, reluctant to leave it.

“Sit down, Enguerrand,” continued Jeanne, “and tell me what

you’ve

been doing this long time. Been very busy, and winning

forensic

fame and gold ? ”

“Well, not exactly,” said Enguerrand, moody once more.

“The fact is,

there’s so much interest required nowadays at

the courts, that

unassisted talent never gets a chance. And you,

Jeanne ?”

“Oh, I don’t complain,” answered Jeanne, lightly. “Of course

it’s

fair-time just now, you know, and we’re always busy then.

But

work will be lighter soon, and then I’ll get a day off, and

we’ll

have a delightful ramble and picnic in the woods, as we

used to

do when we were children. What fun we had in

those old days,

Enguerrand ! Do you remember when we

were quite little tots, and

used to play at executions in the back-

garden, and you were a

bandit and a buccaneer, and all sorts of

dreadful things, and I

used to chop off your head with a paper-

knife ? How pleased dear

father used to be !”

“Jeanne,” said Enguerrand, with some hesitation, “you’ve

touched

upon the very subject that I came to speak to you about.

Do you

know, dear, I can’t help feeling—it may be unreasonable,

but

still the feeling is there—that the profession you have adopted

is not quite—is just a little——”

“Now, Enguerrand !” said Jeanne, an angry flash sparkling in

her

her eyes. She was a little touchy on this subject, the word she

most

affected to despise being also the one she most dreaded—the

adjective “unladylike.”

“Don’t misunderstand me, Jeanne,” went on Enguerrand,

imploringly :

“You may naturally think that, because I should

have succeeded to

the post, with its income and perquisites, had

you relinquished

your claim, there is therefore some personal

feeling in my

remonstrances. Believe me, it is not so. My own

interests do not

weigh with me for a moment. It is on your own

account, Jeanne,

and yours alone, that I ask you to consider

whether the higher

aesthetic qualities, which I know you possess,

may not become

cramped and thwarted by ‘the trivial round, the

common task,’

which you have lightly undertaken. However

laudable a

professional life may be, one always feels that with a

delicate

organism such as woman, some of the bloom may possibly

get rubbed

off the peach.”

“Well, Enguerrand,” said Jeanne, composing herself with an

effort,

though her lips were set hard, “I will do you the justice

to

belive that personal advantage does not influence you, and I will

try to reason calmly with you, and convince you that you are

simply hide-bound by old-world prejudice. Now, take yourself,

for

instance, who come here to instruct me : what does your pro-

fession amount to, when all’s said and

done ? A mass of lies,

quibbles, dodges, and tricks, that would

make any self-respecting

executioner blush ! And even with the

dirty weapons at your

command, you make but a poor show of it.

There was that

wretched fellow you defended only two days ago. (I

was in

court during the trial professional interest, you know.)

Well,

he had his regular alibi all

ready, as clear as clear could be ; only

you must needs go and

mess and bungle the thing up, so that, as I

expected all along,

he was passed on to me for treatment in due

course.

course. You may like to have his opinion—that of a shrewd,

though

unlettered person. ‘It’s a real pleasure, miss,’ he said,

‘to be

handled by you. You knows your work, and

you does your

work—though p’raps I ses

it as shouldn’t. If that blooming fool

of a mouthpiece of

mine’—he was referring to you, dear, in your

capacity of

advocate—’had known his business half as well as you

do yours, I

shouldn’t a bin here now !’ And you know,

Enguerrand, he was

perfectly right.”

“Well, perhaps he was,” admitted Enguerrand. “You see, I

had been

working at a sonnet the night before, and I couldn’t get

the

rhymes right, and they would keep coming into my head in

court

and mixing themselves up with the alibi.

But look here,

Jeanne, when you saw I was going off the track,

you might have

given me a friendly hint, you know—for old times’

sake, if not

for the prisoner’s !”

“I daresay,” replied Jeanne, calmly : “perhaps you’ll tell me

why I

should sacrifice my interests because you’re unable to look

after

yours. You forget that I receive a bonus, over and above

my

salary, upon each exercise of my functions !”

“True,” said Enguerrand, gloomily : “I did forget that. I

wish I had

your business aptitudes, Jeanne.”

“I daresay you do,” remarked Jeanne. “But you see, dear,

how all

your arguments fall to the ground. You mistake a

prepossession

for a logical base. Now if I had gone, like that

Clairette you

used to dangle after, and been waiting-woman to

some grand lady

in a château—a thin-blooded compound of drudge

and

sycophant—then, I suppose, you’d have been perfectly satisfied.

So feminine ! So genteel !”

“She’s not a bad sort of girl, little Claire,” said Enguerrand,

reflectively (thereby angering Jeanne afresh) : “but putting her

aside,—of course you could always beat me at argument, Jeanne ;

you’d

you’d have made a much better lawyer than I. But you know,

dear, how

much I care about you ; and I did hope that on that

account even

a prejudice, however unreasonable, might have some

little weight.

And I’m not alone, let me tell you, in my views.

There was a

fellow in court only to-day, who was saying that

yours was only a

succès d’estime and that woman, as a

naturally

talkative and hopelessly unpunctual animal, could never

be more

than a clever amateur in the profession you have

chosen.”

“That will do, Enguerrand,” said Jeanne, proudly ; “it seems

that

when argument fails, you can stoop so low as to insult me

through

my sex. You men are all alike—steeped in brutish

masculine

prejudice. Now go away, and don’t mention the

subject to me again

till you’re quite reasonable and nice.”

III

Jeanne passed a somewhat restless night after her small scene

with

her cousin, waking depressed and unrefreshed. Though she

had

carried matters with so high a hand, and had scored so

distinctly

all around, she had been more agitated than she had

cared to

show. She liked Enguerrand ; and more especially did

she like his

admiration for her ; and that chance allusion to

Clairette

contained possibilities that were alarming. In embracing

a

professional career, she had never thought for a moment that it

could militate against that due share of admiration to which, as

a

girl, she was justly entitled ; and Enguerrand’s views seemed

this

morning all the more narrow and inexcusable. She rose

languidly,

and as soon as she was dressed sent off a little note

to the Mayor,

saying that she had a nervous headache and felt out

of sorts, and

begging

begging to be excused from attendance on that day ; and the

missive

reached the Mayor just as he was taking his usual place at

the

head of the Board.

“Dear, dear,” said the kind-hearted old man, as soon as he had

read

the letter to his fellow-councilmen : “I’m very sorry. Poor

girl

! Here, one of you fellows, just run round and tell the gaoler

there won’t be any business to-day. Jeanne’s seedy. It’s put off

till to-morrow. And now, gentlemen, the agenda——”

“Really, your worship,” exploded Robinet, “this is simply

ridiculous

!”

“Upon my word, Robinet,” said the Mayor, “I don’t know

what’s the

matter with you. Here’s a poor girl unwell—and a

more hardworking

girl isn’t in the town—and instead of sym-

pathising with her,

and saying you re sorry, you call it ridiculous !

Suppose you had

a headache yourself! You wouldn’t like——”

“But it is ridiculous,” maintained the tanner

stoutly. “Who

ever heard of an executioner having a nervous

headache ? There’s

no precedent for it. And ‘out of sorts,’ too!

Suppose the

criminals said they were out of sorts, and didn’t

feel up to being

executed ?”

“Well, suppose they did,” replied the Mayor, “we’d try and

meet them

halfway, I daresay. They’d have to be executed

some time or

other, you know. Why on earth are you so

captious about trifles ?

The prisoners won’t mind, and I don’t

mind : nobody’s inconvenienced, and everybody’s happy !”

“You’re right there, Mr. Mayor,” put in another councilman.

“This

executing business used to give the town a lot of trouble

and

bother ; now it’s all as easy as kiss-your-hand. Instead of

objecting, as they used to do, and wanting to argue the point and

kick up a row, the fellows as is told off for execution come

skipping along in the morning, like a lot of lambs in Maytime.

And

And then the fun there is on the scaffold ! The jokes, the back-

answers, the repartees ! And never a word to shock a baby !

Why,

my little girl, as goes through the market-place every morn-

ing—on her way to school, you know—she says to me only

yesterday,

she says, ‘Why, father,’ she says, ‘it’s as good as the

play-actors,’ she says.”

“There again,” persisted Robinet, “I object to that too.

They ought

to show a properer feeling. Playing at mummers is

one thing, and

being executed is another, and people ought to

keep ’em separate.

In my father’s time, that sort of thing wasn’t

thought good

taste, and I don’t hold with new-fangled notions.”

“Well, really, neighbour,” said the Mayor, “I think you’re out

of

sorts yourself to-day. You must have got out of bed the

wrong

side this morning. As for a little joke, more or less, we

all

know a maiden loves a merry jest when she’s certain of having

the

last word ! But I’ll tell you what I’ll do, if it’ll please you ;

I’ll go round and see Jeanne myself on my way home, and tell

her—quite nicely, you know—that once in a way doesn’t matter,

but

that if she feels her health won’t let her keep regular

business

hours, she mustn’t think of going on with anything that’s

bad for

her. Like that, don’t you see ? And now, gentlemen,

let’s read

the minutes !”

Thus it came about that Jeanne took her usual walk that

evening with

a ruffled brow and a swelling heart ; and her little

hand opened

and shut angrily as she paced the ramparts. She

couldn’t stand

being found fault with. How could she help

having a headache ?

Those clods of citizens didn’t know what a

highly-strung

sensitive organisation was. Absorbed in her re-

flections, she

had taken several turns up and down the grassy foot-

way, before

she became aware that she was not alone. A youth,

of richer dress

and more elegant bearing than the general run of

the

the Radegundians, was leaning in an embrasure, watching the

graceful

figure with evident interest.

“Something has vexed you, fair maiden ?” he observed, coming

forward

deferentially as soon as he perceived he was noticed ;

“and care

sits but awkwardly on that smooth young brow.”

“Nay, it is nothing, kind sir,” replied Jeanne ; “we girls who

work

for our living must not be too sensitive. My employers

have been

somewhat exigent, that is all. I did wrong to take it

to

heart.”

“Tis the way of the bloated capitalist,” rejoined the young

man

lightly, as he turned to walk by her side. “They grind us,

they

grind us ; perhaps some day they will come under your hands

in

turn, and then you can pay them out. And so you toil and

spin,

fair lily ! And yet methinks those delicate hands show little

trace of labour ?”

“You wrong me, indeed, sir,” replied Jeanne merrily. “These

hands of

mine, that you are so good as to admire, do great execu-

tion

!”

“I can well believe that your victims are numerous,” he

replied ;

“may I be permitted to rank myself among the latest of

them

?”

“I wish you a better fortune, kind sir,” answered Jeanne

demurely.

“I can imagine no more delightful one,” he replied; “and

where do

you ply your daily task, fair mistress ? Not entirely out

of

sight and access, I trust ?”

“Nay, sir,” laughed Jeanne, “I work in the market-place most

mornings, and there is no charge for admission ; and access is

far

from difficult. Indeed, some complain—but that is no

business

of mine. And now I must be wishing you a good

evening.

Nay”—for he would have detained her—”it is not seemly

for an

unprotected

unprotected maiden to tarry in converse with a stranger at this

hour. Au revoir, sir ! If you should happen

to be in the market-

place any morning”——And she tripped lightly

away. The youth,

gazing after her retreating figure, confessed

himself strangely

fascinated by this fair unknown, whose

particular employment, by

the way, he had forgotten to ask ;

while Jeanne, as she sped

homewards, could not help reflecting

that for style and distinction,

this new acquaintance threw into

the shade all the Enguerrands

and others she had met

hitherto—even in the course of business.

IV

The next morning was bright and breezy, and Jeanne was early

at her

post, feeling quite a different girl. The busy little market-

place was full of colour and movement, and the gay patches of

flowers and fruit, the strings of fluttering kerchiefs, and the

piles

of red and yellow pottery, formed an artistic setting to

the quiet

impressive scaffold which they framed. Jeanne was in

short

sleeves, according to the etiquette of her office, and her

round

graceful arms showed snowily against her dark blue skirt

and

scarlet tight-fitting bodice. Her assistant looked at her

with

admiration.

“Hope you’re better, miss,” he said respectfully. “It was just

as

well you didn’t put yourself out to come yesterday ; there was

nothing particular to do. Only one fellow, and he said he didn’t

care ; anything to oblige a

lady !”

“Well, I wish he’d hurry up now, to oblige a lady,” said

Jeanne,

swinging her axe carelessly to and fro : “ten minutes past

the

hour ; I shall have to talk to the Mayor about this.”

The Yellow Book—Vol. III.C

“It’s

“It’s a pity there ain’t a better show this morning,” pursued

the

assistant, as he leant over the rail of the scaffold and spat

meditatively into the busy throng below. “They do say as how

the

young Seigneur arrived at the Château yesterday—him as has

been

finishing his education in Paris, you know. He’s as likely as

not

to be in the market-place to-day ; and if he’s disappointed, he

may go off to Paris again, which would be a pity, seeing the

Château’s been empty so long. But he may go to Paris, or

anywheres else he’s a mind to, he won t see better workmanship

than in this here little town !”

“Well, my good Raoul,” said Jeanne, colouring slightly at the

obvious compliment, “quality, not quantity, is what we aim at

here, you know. If a Paris education has been properly assimi-

lated by the Seigneur, he will not fail to make all the necessary

allowances. But see, the prison-doors are opening at last !”

They both looked across the little square to the prison, which

fronted the scaffold ; and sure enough, a small body of men, the

Sheriff at their head, was issuing from the building, conveying,

or

endeavouring to convey, the tardy prisoner to the scaffold.

That

gentleman, however, seemed to be in a different and less

obliging

frame of mind from that of the previous day ; and at

every pace

one or other of the guards was shot violently into the

middle of

the square, propelled by a vigorous kick or blow from

the struggling

captive. The crowd, unaccustomed of late to such

demonstrations

of feeling, and resenting the prisoner’s want of

taste, hooted

loudly ; but it was not until that ingenious

mediaeval arrangement

known as la marche aux

crapauds had been brought to bear

on him, that the

reluctant convict could be prevailed upon

to present himself

before the young lady he had already so

unwarrantably

detained.

Jeanne’s profession had both accustomed her to surprises

and

and taught her the futility of considering her clients as drawn

from

any one particular class : yet she could hardly hel

feeling some

astonishment on recognising her new acquaintance

of the previous

evening. That, with all his evident amiability of

character, he

should come to this end, was not in itself a special

subject for

wonder ; but that he should have been conversing with

her on the

ramparts at the hour when—after courteously excusing

her

attendance on the scaffold— he was cooling his heels in prison

for another day, seemed hardly to be accounted for, at first

sight.

Jeanne, however, reflected that the reconciling of

apparent contra-

dictions was not included in her official

duties.

The Sheriff, wiping his heated brow, now read the formal

procѐs delivering over the prisoner to the

executioner’s hands ;

“and a nice job we’ve had to get him here,”

he added on

his own account. And the young man, who had

remained

perfectly tractable since his arrival, stepped forward

and bowed

politely.

“Now that we have been properly introduced,” said he

courteously,

“allow me to apologise for any inconvenience you

have been put to

by my delay. The fault was entirely mine, and

these gentlemen are

in no way to blame. Had I known whom I

was to have the pleasure

of meeting, wings could not have con-

veyed me swiftly

enough.”

“Do not mention, I pray, the word inconvenience,” replied

Jeanne

with that timid grace which so well became her : “I only

trust

that any slight discomfort it may be my duty to cause you

before

we part, will be as easily pardoned. And now—for the

morning,

alas ! advances—any little advice or assistance that I

can offer

is quite at your service ; for the situation is possibly new,

and

you may have had but little experience.”

“Faith, none worth mentioning,” said the prisoner, gaily.

“Treat

“Treat me as a raw beginner. Though our acquaintance has been

but

brief, I have the utmost confidence in you.”

“Then, sir,” said Jeanne, blushing, “suppose I were to assist

you

in removing this gay doublet, so as to give both of us more

freedom and less responsibility ?”

“A perquisite of the office ?” queried the prisoner with a smile,

as

he slipped one arm out of the sleeve.

A flush came over Jeanne’s fair brow. “That was un-

generous,” she

said.

“Nay, pardon me, sweet one,” said he, laughing : “twas but a

poor

jest of mine—in bad taste, I willingly admit.”

“I was sure you did not mean to hurt me,” she replied kindly,

while

her fingers were busy in turning back the collar of his shirt.

It

was composed, she noticed, of the finest point lace ; and she

could not help a feeling of regret that some slight error—as

must,

from what she knew, exist somewhere—should compel her to

take

a course so at variance with her real feelings. Her only

comfort

was that the youth himself seemed entirely satisfied with

his

situation. He hummed the last air from Paris during her

minis-

trations, and when she had quite finished, kissed the

pretty fingers

with a metropolitan grace.

“And now, sir,” said Jeanne, “if you will kindly come this

way : and

please to mind the step—so. Now, if you will have

the goodness to

kneel here—nay, the sawdust is perfectly clean ;

you are my first

client this morning. On the other side of the

block you will find

a nick, more or less adapted to the human chin,

though a perfect

fit cannot of course be guaranteed in every case.

So ! Are you

pretty comfortable ?”

“A bed of roses,” replied the prisoner. “And what a really

admirable

view one gets of the valley and the river, from just this

particular point !”

“Charming

“Charming, is it not ?” replied Jeanne. ” I’m so glad you do

justice

to it. Some of your predecessors have really quite vexed

me by

their inability to appreciate that view. It’s worth coming

here

to see it. And now, to return to business for one moment,

—would

you prefer to give the word yourself ? Some people do ;

it’s a

mere matter of taste. Or will you leave yourself entirely

in my

hands ?”

“Oh, in your fair hands,” replied her client, “which I beg you

to

consider respectfully kissed once more by your faithful servant

to command.”

Jeanne, blushing rosily, stepped back a pace, moistening her

palms

as she grasped her axe, when a puffing and blowing behind

caused

her to turn her head, and she perceived the Mayor hastily

ascending the scaffold.

“Hold on a minute, Jeanne, my girl,” he gasped. “Don’t be

in a

hurry. There’s been some little mistake.”

Jeanne drew herself up with dignity. “I’m afraid I don’t

quite

understand you, Mr. Mayor,” she replied in freezing

accents.

“There’s been no little mistake on my part that I’m

aware

of.”

“No, no, no,” said the Mayor, apologetically ; “but on some-

body

else’s there has. You see it happened in this way : this

here

young fellow was going round the town last night ; and he’d

been

dining, I should say, and he was carrying on rather free. I

will

only say so much in your presence, that he was carrying on

decidedly free. So the town-guard happened to come across him,

and he was very high and very haughty, he was, and wouldn’t

give

his name nor yet his address—as a gentleman should, you

know,

when he’s been dining and carrying on free. So our

fellows just

ran him in—and it took the pick of them all their

time to do it,

too. Well, then, the other chap who was in prison—

the

the gentleman who obliged you yesterday, you know—what does

he do

but slip out and run away in the middle of all the row

and

confusion ; and very inconsiderate and ungentlemanly it was

of

him to take advantage of us in that mean way, just when we

wanted

a little sympathy and forbearance. Well, the Sheriff

comes this

morning to fetch out his man for execution, and he

knows there’s

only one man to execute, and he sees there’s only

one man in

prison, and it all seems as simple as A B C—he never

was much of

a mathematician, you know—so he fetches our friend

here along,

quite gaily. And—and that’s how it came about, you

see ; hinc illae lachrymae as the Roman poet has

it. So now I

shall just give this young fellow a good talking to,

and discharge

him with a caution ; and we shan’t require you any

more to-day,

Jeanne, my girl.”

“Now, look here, Mr. Mayor,” said Jeanne severely, “you

utterly fail

to grasp the situation in its true light. All these little

details may be interesting in themselves, and doubtless the press

will take note of them ; but they are entirely beside the point.

With the muddleheadedness of your officials (which I have

frequently remarked upon) I have nothing whatever to do. All I

know is, that this young gentleman has been formally handed over

to me for execution, with all the necessary legal requirements ;

and

executed he has got to be. When my duty has been

performed,

you are at liberty to re-open the case if you like ;

and any ‘little

mistake’ that may have occurred through your

stupidity you can

then rectify at your leisure. Meantime, you’ve

no locus standi

here at all ; in fact, you’ve no business whatever lumbering up

my

scaffold. So shut up and clear out.”

“Now, Jeanne, do be reasonable,” implored the Mayor. “You

women are

so precise. You never will make any allowance for

the necessary

margin of error in things.”

“If

“If I were to allow the necessary margin for all your errors,

Mayor,” replied Jeanne, coolly, ” the

edition would have to be a

large-paper one, and even then the

text would stand a poor chance.

And now, if you don t allow me

the necessary margin to swing

my axe, there may be another

‘little mistake’—”

But at this point a hubbub arose at the foot of the scaffold, and

Jeanne, leaning over, perceived sundry tall fellows, clad in the

livery of the Seigneur, engaged in dispersing the municipal guard

by the agency of well-directed kicks, applied with heartiness

and

anatomical knowledge. A moment later, there strode on to the

scaffold, clad in black velvet, and adorned with his gold chain

of

office, the stately old seneschal of the Château, evidently in

a

towering passion.

“Now, mark my words, you miserable little bladder-o’-lard,” he

roared at the Mayor (whose bald head certainly shone provokingly

in the morning sun), “see if I don’t take this out of your skin

presently !” And he passed on to where the youth was still

kneeling, apparently quite absorbed in the view.

“My lord,” he said, firmly though respectfully, “your hair-

brained

folly really passes all bounds. Have you entirely lost your

head

?”

“Faith, nearly,” said the young man, rising and stretching him-

self. “Is that you, old Thibault ? Ow, what a crick I’ve got

in

my neck ! But that view of the valley was really de-

lightful

!”

“Did you come here simply to admire the view, my lord ?”

inquired

Thibault severely.

“I came because my horse would come,” replied the young

Seigneur

lightly : “that is, these gentlemen here were so pressing ;

they

would not hear of any refusal ; and besides, they forgot to

mention what my attendance was required in such a hurry for.

And

And when I got here, Thibault, old fellow, and saw that divine

creature—nay, a goddess, dea certé—so

graceful, so modest, so

anxious to acquit herself with credit——

Well, you know my

weakness ; I never could bear to disappoint a

woman. She had

evidently set her heart on taking my head ; and as

she had my

heart already——”

“I think, my lord,” said Thibault with some severity, “you

had

better let me escort you back to the Château. This appears

to be

hardly a safe place for light-headed and susceptible persons !”

Jeanne, as was natural, had the last word. “Understand me,

Mr.

Mayor,” said she, ” these proceedings are entirely irregular.

I

decline to recognise them, and when the quarter expires I shall

claim the usual bonus !”

V

When, an hour or two later, an invitation arrived—courteously

worded, but significantly backed by an escort of half-a-dozen

tall

archers—for both Jeanne and the Mayor to attend at the

Château

without delay, Jeanne for her part received it with

neither sur-

prise nor reluctance. She had felt it especially

hard that the only

two interviews fate had granted her with the

one man who had

made some impression on her heart, should be

hampered, the one

by considerations of propriety, the other by

the conflicting claims

of her profession and its duties. On this

occasion, now, she

would have an excellent chaperon in the Mayor

; and business

being over for the day, they could meet and unbend

on a common

social footing. The Mayor was not at all surprised

either, consider-

ing what had gone before ; but he was

exceedingly terrified, and

sought some consolation from Jeanne as

they proceeded together

to

to the Château. That young lady’s remarks, however, could

hardly be

called exactly comforting.

“I always thought you’d put your foot in it some day, Mayor,”

she

said. “You are so hopelessly wanting in system and method.

Really, under the present happy-go-lucky police arrangements, I

never know whom I may not be called upon to execute. Between

you

and my cousin Enguerrand, life is hardly safe in this town.

And

the worst of it is, that we other officials on the staff have to

share in the discredit.”

“What do you think they’ll do to me, Jeanne ?” whimpered

the Mayor,

perspiring freely.

“Can’t say, I’m sure,” pursued the candid Jeanne. “Of course,

if

it’s anything in the rack line of business,

I shall have to super-

intend the arrangements, and then you can

feel sure you’re in

capable hands. But probably they’ll only fine

you pretty smartly,

give you a month or two in the dungeons, and

dismiss you from

your post ; and you will hardly grudge any

slight personal incon-

venience resulting from an arrangement so

much to the advantage

of the town.”

This was hardly reassuring, but the Mayor’s official reprimand

of

the previous day still rankled in this unforgiving young person’s

mind.

On their reaching the Château, the Mayor was conducted aside,

to be

dealt with by Thibault ; and from the sounds of agonised

protestation and lament which shortly reached Jeanne’s ears, it

was evident that he was having a mauvais quart

d’heure. The

young lady was shown respectfully into

a chamber apart, where

she had hardly had time to admire

sufficiently the good taste of

the furniture and the magnificence

of the tapestry with which the

walls were hung, when the Seigneur

entered and welcomed her

with a cordial grace that put her

entirely at her ease.

“Your

“Your punctuality puts me to shame, fair mistress,” he said,

“considering how unwarrantably I kept you waiting this morning,

and how I tested your patience by my ignorance and awkward-

ness.”

He had changed his dress, and the lace round his neck was even

richer than before. Jeanne had always considered one of the

chief

marks of a well-bred man to be a fine disregard for the

amount of

his washing-bill ; and then with what good taste he

referred to

recent events—putting himself in the wrong, as a

gentleman should

!

“Indeed, my lord,” she replied modestly, “I was only too

anxious to

hear from your own lips that you bore me no ill-will

for the part

forced on me by circumstances in our recent interview.

Your

lordship has sufficient critical good sense, I feel sure, to

distinguish between the woman and the official.”

“True, Jeanne,” he replied, drawing nearer; “and while I

shrink from

expressing, in their fulness, all the feelings that the

woman

inspires in me, I have no hesitation—for I know it will

give you

pleasure—in acquainting you with the entire artistic

satisfaction

with which I watched you at your task !”

“But, indeed” said Jeanne, “you did not see me at my best.

In fact,

I can’t help wishing—it’s ridiculous, I know, because the

thing

is hardly practicable—but if I could only have carried my

performance quite through, and put the last finishing touches to

it, you would not have been judging me now by the mere

‘blocking-in’ of what promised to be a masterpiece !”

“Yes, I wish it could have been arranged somehow,” said the

Seigneur

reflectively; “but perhaps it’s better as it is. I am con-

tent

to let the artist remain for the present on trust, if I may only

take over, fully paid up, the woman I adore !”

Jeanne felt strangely weak. The official seemed oozing out at

her

her fingers and toes, while the woman’s heart beat even more dis-

tressingly.

“I have one little question to ask,” he murmured (his arm

was about

her now). “Do I understand that you still claim your

bonus ?”

Jeanne felt like water in his strong embrace ; but she nerved

herself to answer faintly but firmly : “Yes !”

“Then so do I,” he replied, as his lips met hers.

*****

Executions continued to occur in St. Radegonde ; the Rade-

gundians

being conservative and very human. But much of the

innocent

enjoyment that formerly attended them departed after

the fair

Chatelaine had ceased to officiate. Enguerrand, on suc-

ceeding

to the post, wedded Clairette, she being (he was heard to

say) a

more suitable match in mind and temper than others of

whom he

would name no names. Rumour had it, that he found

his match and

something over ; while as for temper—and mind

(which she gave him

in bits)—— But the domestic trials of high-

placed officials have

a right to be held sacred. The profession, in

spite of his best

endeavours, languished nevertheless. Some said

that the scaffold

lacked its old attraction for criminals of spirit ;

others, more

unkindly, that the headsman was the innocent cause,

and that

Enguerrand was less fatal in his new sphere than

formerly, when

practising in the criminal court as advocate for

the defence.

Credo

By Arthur Symons

EACH, in himself, his hour to be and cease

Endures alone, yet few there be who dare

Sole with himself his single burden bear,

All the long day until the night’s release.

Yet, ere the night fall, and the shadows close,

This labour of himself is each man’s lot ;

All a man hath, yet living, is forgot,

Himself he leaves behind him when he goes.

If he have any valiancy within,

If he have made his life his very own,

If he have loved and laboured, and have known

A strenuous virtue, and the joy of sin ;

Then, being dead, he has not lived in vain,

For he has saved what most desire to lose,

And he has chosen what the few must choose,

Since life, once lived, returns no more again.

For

For of our time we lose so large a part

In serious trifles, and so oft let slip

The wine of every moment at the lip

Its moment, and the moment of the heart.

We are awake so little on the earth,

And we shall sleep so long, and rise so late,

If there is any knocking at that gate

Which is the gate of death, the gate of birth.

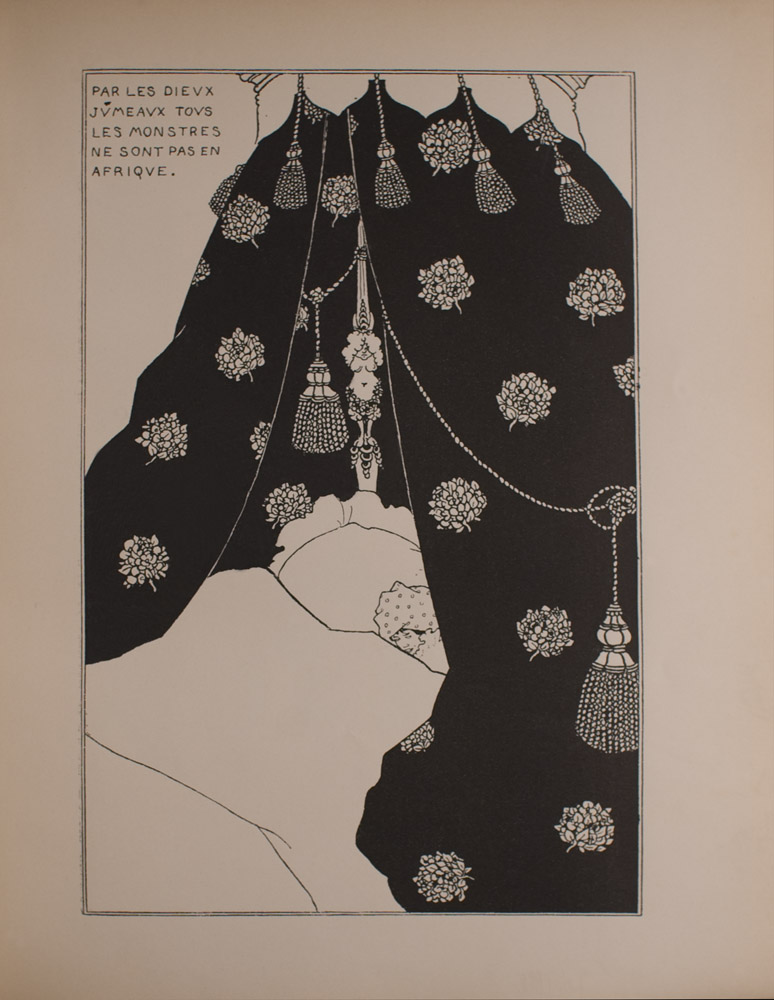

Four Drawings

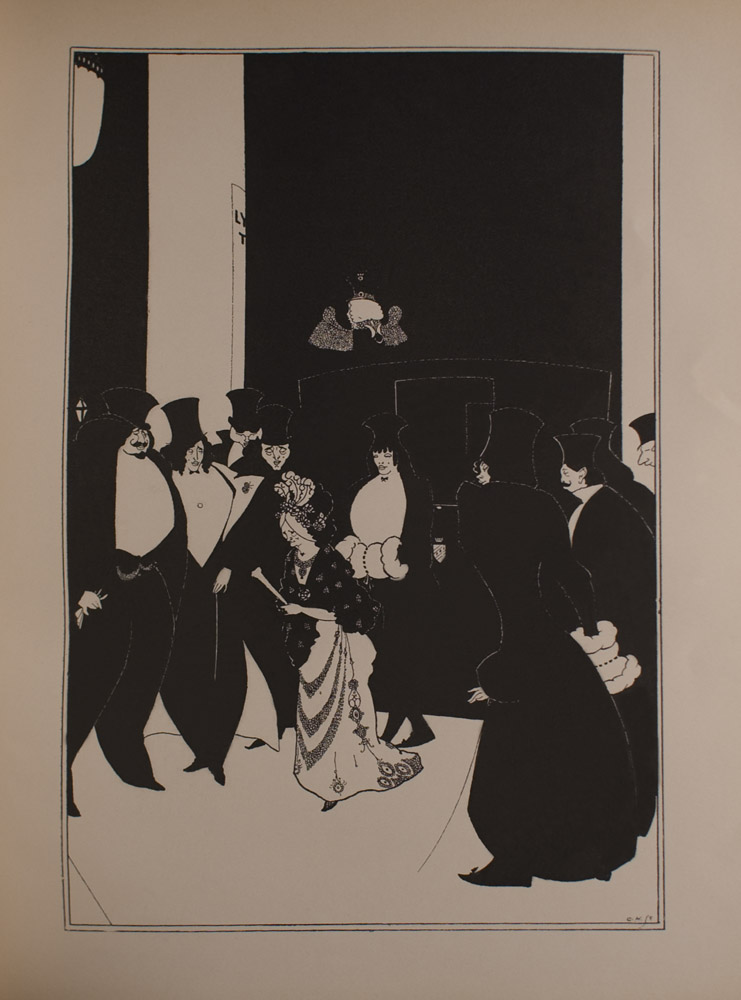

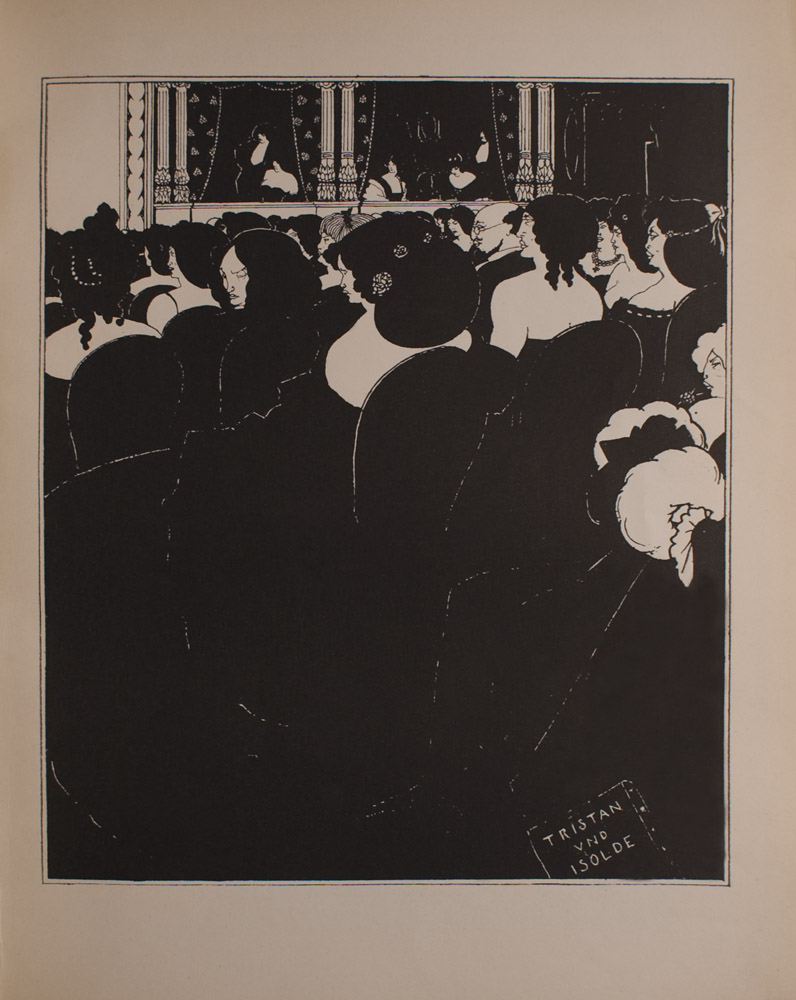

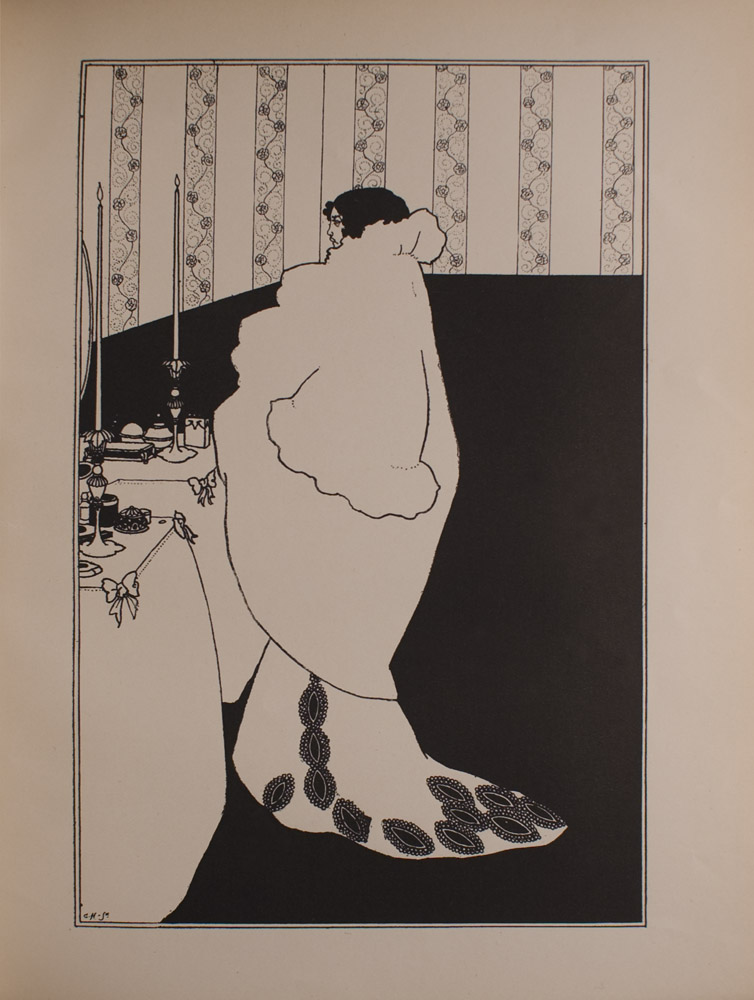

I. Portrait of Himself

II. Lady Gold’s Escort

III. The Wagnerites

IV. La Dame aux Camelias

White Magic

By Ella D’Arcy

I SPENT one evening last summer with my friend Mauger,

pharmacien in the little town of

Jacques-le-Port. He pro-

nounces his name Major, by-the-bye, it

being a quaint custom of

the Islands to write proper names one

way and speak them another,

thus serving to bolster up that old,

old story of the German

savant’s account of the difficulties of

the English language “where

you spell a man’s name Verulam,” says

he reproachfully, “and

pronounce it Bacon.”

Mauger and I sat in the pleasant wood-panelled parlour behind

the

shop, from whence all sorts of aromatic odours found their

way in

through the closed door to mingle with the fragrance of

figs,

Ceylon tea, and hot gôches-à-beurre

constituting the excellent

meal spread before us. The large

old-fashioned windows were

wide open, and I looked straight out

upon the harbour, filled with

holiday yachts, and the wonderful

azure sea.

Over against the other islands, opposite, a gleam of white

streaked

the water, white clouds hung motionless in the blue sky,

and a

tiny boat with white sails passed out round Falla Point. A

white

butterfly entered the room to flicker in gay uncertain curves

above the cloth, and a warm reflected light played over the

slender

rat-tailed forks and spoons, and raised by a tone or two

the colour

of

of Mauger’s tanned face and yellow beard. For, in spite of a

sedentary profession, his preferences lie with an out-of-door

life,

and he takes an afternoon off whenever practicable, as he

had done

that day, to follow his favourite pursuit over the

golf-links at Les

Landes.

While he had been deep in the mysteries of teeing and putting,

with

no subtler problem to be solved than the judicious selection of

mashie and cleek, I had explored some of the curious cromlechs or

pouquelayes scattered over this part of the

island, and my thoughts

and speech harked back irresistibly to

the strange old religions and

usages of the past.

“Science is all very well in its way,” said I ; “and of course

it’s

an inestimable advantage to inhabit this so-called nineteenth

century ; but the mediaeval want of science was far more pic-

turesque. The once universal belief in charms and portents, in

wandering saints, and fighting fairies, must have lent an

interest

to life which these prosaic days sadly lack. Madelon

then would

steal from her bed on moonlight nights in May, and

slip across the

dewy grass with naked feet, to seek the

reflection of her future

husband’s face in the first running

stream she passed ; now, Miss

Mary Jones puts on her bonnet and

steps round the corner, on

no more romantic errand than the

investment of her month’s

wages in the savings bank at two and a

half per cent.”

Mauger laughed. “I wish she did anything half so prudent !

That has

not been my experience of the Mary Joneses.”

“Well, anyhow,” I insisted, “the Board school has rationalised

them.

It has pulled up the innate poetry of their nature to replace

it

by decimal fractions.”

To which Mauger answered “Rot !” and offered me his

cigarette-case.

After the first few silent whiffs, he went on as

follows : “The

innate poetry of Woman ! Confess now, there is

no

no more unpoetic creature under the sun. Offer her the sublimest

poetry ever written and the Daily

Telegraph’s latest article on

fashions, or a good

sound murder or reliable divorce, and there’s no

betting on her

choice, for it’s a dead certainty. Many men have

a love of

poetry, but I’m inclined to think that a hundred women

out of

ninety-nine positively dislike it.”

Which struck me as true. “We’ll drop the poetry, then,” I

answered ;

“but my point remains, that if the girl of to-day has no

superstitions, the girl of to-morrow will have no beliefs. Teach

her to sit down thirteen to table, to spill the salt, and walk

under

a ladder with equanimity, and you open the door for Spencer

and

Huxley, and—and all the rest of it,” said I, coming to an

impotent

conclusion.

“Oh, if superstition were the salvation of woman—but you are

thinking of young ladies in London, I suppose ? Here, in the

Islands, I can show you as much superstition as you please. I’m

not sure that the country-people in their heart of hearts don’t

still

worship the old gods of the pouquelayes. You would not, of

course, find any one

to own up to it, or to betray the least glimmer

of an idea as to

your meaning, were you to question him, for ours is

a shrewd

folk, wearing their orthodoxy bravely ; but possibly the

old

beliefs are cherished with the more ardour for not being openly

avowed. Now you like bits of actuality. I’ll give you one, and

a

proof, too, that the modern maiden is still separated by many a

fathom of salt sea-water from these fortunate isles.

“Some time ago, on a market morning, a girl came into

the shop, and

asked for some blood from a dragon. ‘Some what ?’

said I, not

catching her words. ‘Well, just a little blood from a

dragon,’

she answered very tremulously, and blushing. She meant

of course,

‘dragon’s blood,’ a resinous powder, formerly much used

in

medicine, though out of fashion now.

The Yellow Book—Vol. III. D

“She

“She was a pretty young creature, with pink cheeks and dark

eyes,

and a forlorn expression of countenance which didn’t seem at

all

to fit in with her blooming health. Not from the town, or I

should have known her face ; evidently come from one of the

country parishes to sell her butter and eggs. I was interested to

discover what she wanted the ‘dragon’s blood’ for, and after a

certain amount of hesitation she told me. ‘They do say it’s good,

sir, if anything should have happened betwixt you an’ your young

man. ‘Then you have a young man ?’ said I. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘And

you’ve fallen out with him ?’ ‘Yes, sir.’ And tears rose

to her

eyes at the admission, while her mouth rounded with awe

at my

amazing perspicacity. And you mean to send him some

dragon’s

blood as a love potion ?’ ‘No, sir ; you’ve got to mix

it with

water you ve fetched from the Three Sisters Well, and

drink it

yourself in nine sips on nine nights running, and get into

bed

without once looking in the glass, and then if you’ve done

everything properly, and haven’t made any mistake, he’ll come

back to you, an’ love you twice as much as before.’ ‘And la

mѐre

Todevinn (Tostevin) gave you that precious recipe, and

made you

cross her hand with silver into the bargain,’ said I

severely ;

on which the tears began to flow outright.

“You know the old lady,” said Mauger, breaking off his narra-

tion,

” who lives in the curious stone house at the corner of the

market-place ? A reputed witch who learned both black and

white

magic from her mother, who was a daughter of Hélier

Mouton, the

famous sorcerer of Cakeuro. I could tell you some

funny stories

relating to la Mѐre Todevinn, who numbers more

clients among the

officers and fine ladies here than in any other

class ; and very

curious, too, is the history of that stone house, with

the

Brancourt arms still sculptured on the side. You can see them,

if

you turn down by the Water-gate. This old sinister-looking

building,

building, or rather portion of a building, for more modern houses

have been built over the greater portion of the site, and now

press

upon it from either hand, once belonged to one of the

finest man-

sions in the islands, but through a curse and a crime

has been

brought down to its present condition ; while the

Brancourt

family have long since been utterly extinct. But all

this isn’t the

story of Elsie Mahy, which turned out to be the

name of my little

customer.

“The Mahys are of the Vauvert parish, and Pierre Jean, the

father of

this girl, began life as a day-labourer, took to tomato-

growing

on borrowed capital, and now owns a dozen glass-houses

of his

own. Mrs. Mahy does some dairy-farming on a minute

scale, the

profits of which she and Miss Elsie share as pin-money.

The young

man who is courting Elsie is a son of Toumes the

builder. He

probably had something to do with the putting up of

Mahy’s

greenhouses, but anyhow, he has been constantly over at

Vauvert

during the last six months, superintending the alterations

at de

Câterelle’s place.

“Toumes, it would seem, is a devoted but imperious lover, and

the

Persian and Median laws are as butter compared with the

inflexibility of his decisions. The little rift within the lute,

which

has lately turned all the music to discord, occurred last

Monday

week—bank-holiday, as you may remember. The Sunday

school

to which Elsie belongs—and it’s a strange anomaly, isn’t

it, that

a girl going to Sunday school should still have a rooted

belief in

white magic ?—the school was to go for an outing to

Prawn Bay,

and Toumes had arranged to join his sweetheart at the

starting-

point. But he had made her promise that if by any

chance he

should be delayed, she would not go with the others,

but would

wait until he came to fetch her.

“Of course, it so happened that he was detained, and, equally of

course.

course, Elsie, like a true woman, went off without him. She did

all

she knew to make me believe she went quite against her own

wishes, that her companions forced her to go. The beautifully

yielding nature of a woman never comes out so conspicuously as

when she is being coerced into following her own secret desires.

Anyhow, Toumes, arriving some time later, found her gone. He

followed on, and under ordinary circumstances, I suppose, a sharp

reprimand would have been considered sufficient. Unfortunately,

the young man arrived on the scene to find his truant love deep

in the frolics of kiss-in-the-ring. After tea in the Câterelle

Arms, the whole party had adjourned to a neighbouring meadow,

and

were thus whiling away the time to the exhilarating strains of

a