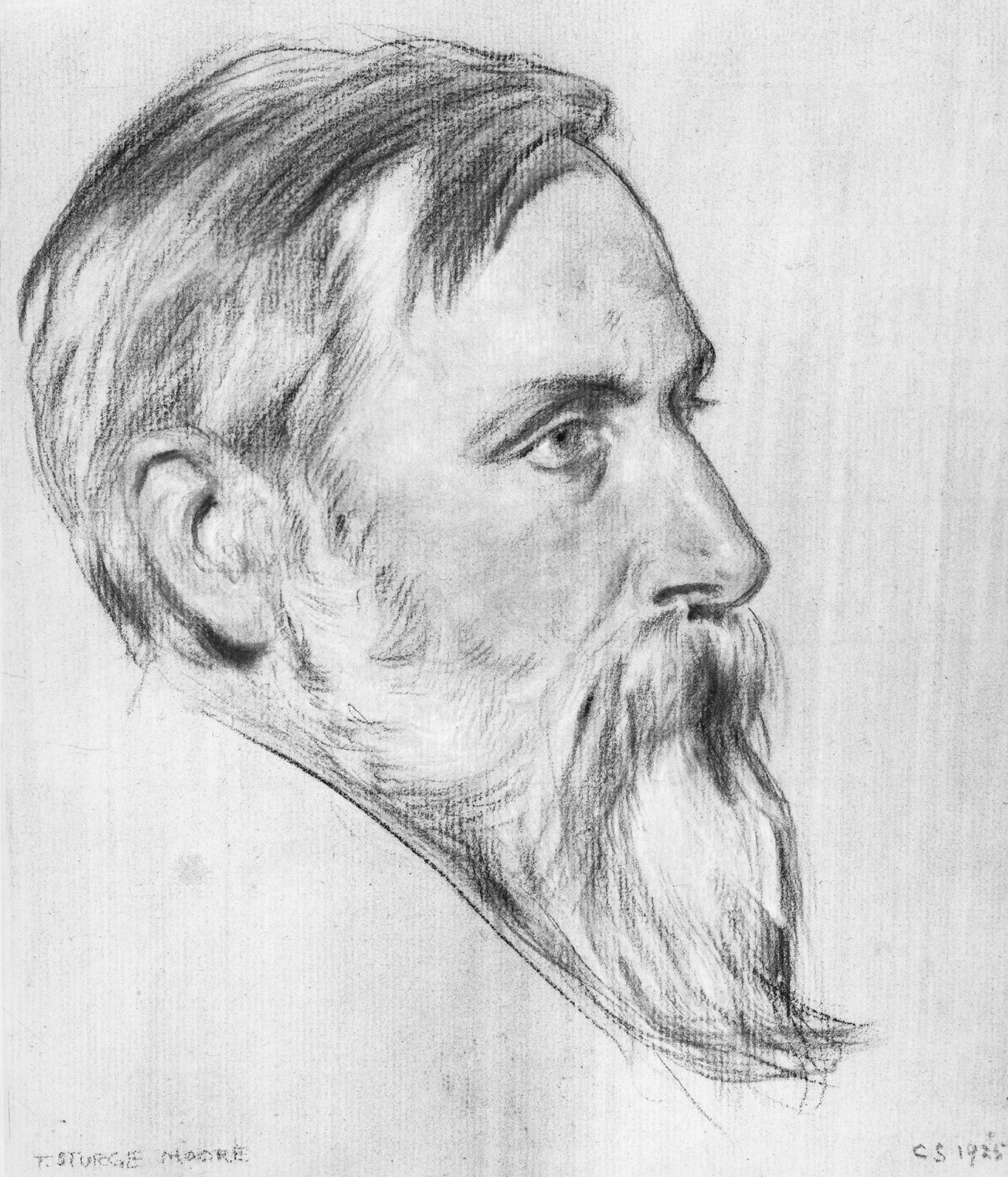

Thomas Sturge Moore

(1870 – 1944)

In April 1922, T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) invited T. Sturge Moore to contribute to the inaugural issue of The Criterion (1922–1935). Eliot’s vision was to create a new magazine with the best critical writing that was on offer. Although he had not previously met Sturge Moore, the elder poet and critic was for Eliot preeminent among his generation, no doubt for his classicist credentials. “I have great respect for your judgement and taste, and count it of the highest importance to secure your support” (Letters I, 656). Sturge Moore would contribute a long essay, spread across two issues, on modern treatments of the Tristan and Isolde legend.

Sturge Moore is often classed as a Victorian poet on the grounds of his first, slender collection of poetry, The Vinedresser and other Poems, published in 1899. But his career spans nearly six decades, with his most important and innovative work appearing after the turn of the twentieth century. He was also versatile in several media: poetry and drama, wood engraving, book and stage design, translation, and art criticism. Not only was his work held in high regard by his contemporaries, his prolific output meant that he knew everyone of importance in the artistic and cultural world of his time.

Born in Hastings on 4 March 1870, Thomas Sturge Moore was the first child of Daniel Moore and Henriette Sturge and elder brother of the Cambridge philosopher G.E. Moore. He grew up in the sumptuous suburban area of Upper Norwood, in south-east London near the Crystal Palace. Though the family had strong Baptist ties, the young Thomas was a self-professed atheist from a fairly young age. Educated at home for some time because he was thought to have a weak constitution, he attended Dulwich College from 1879 to 1884. After graduating, he went to the Croydon Art School, where he was taught by Charles Shannon (1863-1937). Two years later he moved to Lambeth Art School, where he met Charles Ricketts (1866-1931). Becoming friends, Sturge Moore soon joined their circle at The Vale, Chelsea. He fell under the influence of their connoisseurship and artistic taste, while they encouraged his artistic development, especially in wood-engraving, a traditional art form they sought to revive. According to Edith Cooper (1862-1913), Ricketts and Shannon saw Moore as a new Ruskin whose critical acuity would help them spread their message (Legge 187). In return, they provided him with opportunities to place his creative work. His art appeared in The Dial, The Pageant, The Dome (1897–1900), and The Venture. He also edited Shakespeare and Wordsworth for The Vale Press, and Ricketts included a series of Moore’s woodcuts in the “First Exhibition of Original Wood-Engraving” at The Dutch Gallery in Brook Street, Hanover Square in 1898.

His poetic output of this time was considerable, but it consisted mainly of autobiographically-tinted love poems that were never published. The poems were addressed to Maria Appia, his French cousin, whom he was to marry in 1903 after a long courtship. The first of his published literary works appeared in the second issue of The Dial (1892). The pieces betray a powerful early Symbolist and fin-de-siècle influence: of the nine poems, two refer to Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891) and one to Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1834-1898). The true nature of his interests, however, soon came to the fore. The production of a series of woodcuts, Metamorphoses of Pan and other Woodcuts (1895), marked his fascination with classical imagery and bucolic scenes drawn from Ovid. His “Pan Mountain,” which was first printed in the third issue of The Dial (1893), and “Pan Island,” published in the fifth issue of The Dial (1897), were to be among his most enduring early images. The Print-Collector’s Quarterly described them as woodcuts executed “in a mystic manner,” appreciating their “carefully wrought” manner and “emotional intensity” (Furst 276). His poetry, too, turned to classical subjects, with poems like “Chorus of Grecian Girls,” “Danaë,” “Pallas and the Centaur: After a Picture by Botticelli,” “A Prayer to Venus,” and “The Centaur,” which were published in The Dial and The Pageant.

None of these poems was included in The Vinedresser (1899). Published by Ernest Oldmeadow’s (1867-1949) Unicorn Press in a dainty volume in bright green cloth, the collection brought together different, more sentimental work. The volume attracted some positive attention, among others from Sturge Moore’s friend Laurence Binyon (1869-1943), who wrote that it was “a more remarkable gift than any first book of verse in recent years” (“Mr. Sturge Moore’s Poems” 54). W. B. Yeats (1865-1939) reacted with surprise, and maybe a tinge of jealousy, when he discovered The Vinedresser a year or so later. Yeats figured he had surrounded himself with the best poets of his day in the Rhymers’ Club, and could not understand how this remarkable poet had escaped his attention (Yeats 495-96). Eager to make the acquaintance of this new young poet, Yeats met Sturge Moore in late 1900 at Binyon’s flat in Westminster. The two became close friends and collaborators until Yeats’s death. Sturge Moore went on to design nearly all of the covers for Yeats’s Macmillan books, capturing with alluring geometric simplicity the esoteric symbolism of the poet’s work. The most striking of this work is his exquisite rendering, in gold leaf on green cloth, of Thoor Ballylee, Yeats’s home in the West of Ireland, for The Tower (1928).

Stimulated by these new connections, the early 1900s became Sturge Moore’s most prolific period. In 1903 and 1904 Sturge Moore issued no less than six pamphlets with Duckworth. Issued in a uniform, paper-covered format, these contained the culmination of his early creative work on classical subjects: The Centaur’s Booty (1903), The Rout of the Amazons (1903), The Gazelles and other Poems (1904), Pan’s Prophecy (1904), To Leda, and other Odes (1904), and Theseus, Medea and Lyrics (1904). During the same period, The Vale Press issued Danaë: A Poem (1904) and with the Unicorn Press he published two more dramas: Aphrodite against Artemis: A Tragedy (1901) and Absalom: A Chronicle Play in Three Acts (1903). These publications firmly established him as a modern lyric poet and writer of verse dramas.

The friend who helped Sturge Moore’s evolution away from The Dial and its purely nineties aesthetics was the poet and dramatist R. C. Trevelyan (1872-1951), an elegant young man two years his junior, whom he had met in 1894. The two authors soon engaged in exchanging frank criticism of each other’s work as well as that of others, in person or in their correspondence, which they kept up, at times quite intensely, during their lifelong friendship. The result was a total rejection (as he told Trevelyan) of the “watery verse” of much nineteenth-century poetry, and of the “mooning in nature” of the spiritualized poetry of Wordsworth, Browning and Tennyson. Instead, Sturge Moore looked towards the sharper expression and the humanism of Rossetti, Arnold, and Flaubert (qtd. in Gwynn 82). In Edith Cooper’s estimation, when she and Katharine Bradley met Sturge Moore in 1901, they thought he was “intensely modern, & in no wise decadent” (qtd in Field, 78).

It is no exaggeration to say that Sturge Moore worked to bring nineties aestheticism into the twentieth century. He was no modernist in the strict sense of the term. Instead, he worked to make the ancients new. His fascination with Hellenism created a new focal point for his defence of Beauty with capital B that would permeate his various artistic activities, including his work for the theatre. In the early years of the twentieth century, he was involved with no less than three theatrical organizations: The Masquers’ Society, co-founded with Yeats and Arthur Symons (1865-1945) in 1905, which failed to come off the ground however; the Literary Theatre Club, which staged one of his plays in 1906; and the Stage Society, to which he was elected a member in 1908.

Moore’s preoccupation with Beauty ultimately led to the formulation of a classical aesthetics which found its first formulation in Art and Life, a collection of essays published in 1910. Critically ruminating on the life and work of William Blake and Gustave Flaubert, he sought to frame, as Binyon observed in his review, “a real and fundamental relation between art and life” (“Art and Life” 229). The problem he was addressing was how to bring the fin-de-siècle celebration of the personality and subjectivity of the artist into alignment with the classical notion that beauty is intrinsic, objective and absolute. The outcome was an original philosophy that found wide-spread sympathy. Arnold Bennett (1867-1931), writing under the pseudonym Jacob Tonson, praised Art and Life for “making the English artist a conscious artist” (494), and Wyndham Lewis called it an “admirable book” (44). Notably, Moore’s ideas prefigured T. S. Eliot’s more famous remarks on the impersonality of the artist.

A year after the publication of Art and Life, Sturge Moore was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Meanwhile, he moved into new literary circles. He became associated with the group around the magazine The New Age (1894–1938), edited by A.R. Orage (1873-1934), noted for its socialist ideals, Fabian connections, and Nietzschean thought. In 1912, he also met, through Yeats, the Bengali poet Rabrindranath Tagore (1861-1941), and later translated some of his work. In 1914, he was invited by Ezra Pound (1885-1972) to the famous Peacock Dinner in honour of Wilfred Scawen Blunt (1840-1922). The event was a piece of literary propaganda co-opted by Pound to showcase the transition of one generation to the next, as is evident from the photograph that was published in the newspapers. The photo shows the elder poet flanked on one side by Sturge Moore, Yeats and Victor Plarr (1863-1929) and on the other by the young Imagists, Pound, Richard Aldington (1892-1962) and F. S. Flint (1885-1960).

In 1912, Sturge Moore and his family (now with two children, Daniel, born 1905, and Riette, born 1907) moved from 20 St. James Square, Holland Park into a large townhouse, 40 Well Walk, Hampstead. The house, which had formerly belonged to the painter John Constable, would be his semi-permanent home for the rest of his life. The Sea is Kind, his first poetry book since the Duckworth volumes, was published by Grant Richards in 1914. In 1919, Grant Richards brought out Some Soldier Poets. It was the first critical assessment of the War Poets, which fast became Sturge Moore’s most successful and most widely read book of criticism.

In the 1920s, public recognition complemented the esteem in which he was held by his fellow writers and artists. He was a regular contributor to the Times Literary Supplement (1902), The Criterion and various other journals. He was also a sought-after speaker, delivering lectures on aesthetics, art and poetry up and down the country. He was put on the civil list, receiving a pension of £75 per annum in 1920, and in 1930 his name was featured on the shortlist to replace Robert Bridges (1844-1930) as the poet laureate. This honour, however, went to his friend and fellow Venture contributor John Masefield (1878-1967).

The twenties were also an important decade for Sturge Moore’s dramatic work, which was developing in new directions. Beginning in 1920, he published Tragic Mothers, which included two plays based on Greek mythology, Medea and Niobe, along with Tyrfing, on subject matter extracted from the Old Norse Sagas. He followed with the biblical drama Judas, begun in 1910 but not published until 1923; a drama set in the Spanish Golden Age, Roderigo of Bolivar (1925), based on an incident from Corneille’s Le Cid; and He Will Not Come (probably dating from this period, but not published until 1933), a version of Don Juan whose experimental nature is suggested in the subtitle: “A Drama to Be Overheard from Behind a Curtain.”

In 1927, Sturge Moore inaugurated his Friday evenings at Well Walk. Taking over from Shannon and Ricketts’ Friday evenings in The Vale, and from Yeats’s Monday evenings, he invited like-minded artists, writers and friends to his Friday-night “Bachelor Evenings” to read poetry and discuss art old and new. Among these were John Coply (1875-1950), John Gawsworth (1912-1970), Wilfred Gibson (1878-1962), Edward Lowbury (1913-2007), Andrew Young (1885-1971), the publisher Stanley Unwin (1884-1968), and George Orwell (1903-1950). In this period, he reworked a series of lectures on aesthetics into Armour for Aphrodite (1929). This book contains his most comprehensive expression on classicism and the impersonality of art.

In 1933, he became a member of the Art Workers Guild and regularly spoke at their meetings on subjects like “Is there a Philosophy of Art?” and “Can an artist do what he likes, or are there Universal Principles of Art?”. In 1931, he met the Indian Monk Shri Purohit Swami (1882-1940), whom he introduced to Yeats. Between 1931 and 1933, the Collected Edition, containing all of his poems and some of his verse plays, appeared in four volumes with Macmillan; it was followed by the Selected Poems in 1934. After that he continued to write poetry and plays: Mystery and Tragedy in 1930; Nine Poems, also in 1930; and his final volume, The Unknown Known, and a dozen odd Poems in 1939. Among his most important work of the period, however, is his chronicling of the fin-de-siècle. As the literary executor of both Michael Field (Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper) and Charles Ricketts, he made selections of their personal papers, which appeared as Works and Days: From the Journal of Michael Field (1933) and Self-Portrait: Taken from the Letters and Journals of Charles Ricketts (1939).

Although the 1930s continued to be a period of high productivity, his health was slowly deteriorating. By 1942 he was chronically ill, suffering a series of heart attacks. On 18 July 1944 he died from a kidney infection following prostate surgery at St. Andrews Cottage, a convalescent home in the former Almshouses run by the Mercy Sisters, in Clewer near Windsor. Despite the high recognition he enjoyed during his lifetime, his work fell out of print. Macmillan never re-issued the Collected Edition and with the popularity of modernism eclipsing other literary modes after the Second World War, Sturge Moore’s literary reputation waned. His name, however, lives on among collectors of rare books because of the many cover designs that he did for his own books, and those of Cloudesley Brereton (1863-1937), Tagore, Yeats and, most famously, H. P. R. Finberg’s translation of Villiers de l’Isle Adam’s Axël (1925), as well as his for involvement with The Vale Press.

© 2021 Dr. Wim Van Mierlo, Lecturer in Publishing and English, Lougborough University, UK

Selected Publications by T. Sturge Moore

- Absalom: A Chronicle Play in Three Acts. London: At the Sign of the Unicorn, 1903.

- Albert Durer. London: Duckworth; New York: Charles Scribner, 1905.

- Altdorfer. London: At the Sign of the Unicorn, 1900.

- Aphrodite against Artemis: A Tragedy. London: At the Sign of the Unicorn, 1901.

- Armour for Aphrodite. London: Grant Richards and Humphrey Toulmin at the Cayme Press, 1929.

- Art and Life. London: Methuen, 1910.

- The Centaur’s Booty. London: Duckworth, 1903.

- Correggio. London: Duckworth; New York: Charles Scribner, 1906.

- Danaë: A Poem. London: Duckworth, 1903.

- The Gazelles and other Poems. London: Duckworth, 1904.

- Hark to These Three Talk about Style. London: Elkin Mathews, 1915.

- He Will Not Come: A Drama to Be Overheard from Behind a Curtain, in Collected Edition: Fourth Volume. London: Macmillan, 1933, pp. 137-60.

- Judas. London: Grant Richards, 1923.

- The Little School: A Posy of Rhymes. London: The Eragny Press, 1905.

- Mariamne: A Conflict. London: Duckworth, 1911.

- Metamorphoses of Pan and other woodcuts. London: privately printed for The Dutch Gallery, 1895.

- Mystery and Tragedy: Two Dramatic Poems. London: The Cayme Press, 1930.

- Ought Art to Be Taught in Schools. Birmingham: Central School of Arts and Crafts, 1926.

- Pan’s Prophecy. London: Duckworth, 1904.

- The Poems of T. Sturge Moore: Collected Edition. 4 vols. London: Macmillan, 1931-1933.

- The Powers of the Air. London: Grant Richards, 1920.

- Roderigo of Bolivar. New York: William Edwin Rudge, 1925.

- The Rout of the Amazons. London: Duckworth, 1903.

- The Sea Is Kind. London: Grant Richards, 1914.

- Selected Poems. London: Macmillan, 1934.

- Some Soldier Poets. London: Grant Richards, 1919

- “The Story of Tristram and Isolt in Modern Poetry”, The Criterion, vol. 1, no.1, 1922, pp. 34-49 and vol. 1, no. 2, 1923, pp. 170-87.

- Theseus, Medea and Lyrics. London: Duckworth, 1904.

- Two Poems. London: privately printed by Folkard, 1893.

- The Unknown Known and a Dozen Odd Poems. London: Martin Secker for The Richards Press, 1939.

- The Vinedresser and other Poems. London: At the Sign of the Unicorn, 1899.

Selected Publications about T. Sturge Moore and Works

- Binyon, Laurence. “Art and Life.” Saturday Review, 20 August 1910, p. 229.

- ––. “Mr. Sturge Moore’s Poems.” The Literary Year-Book and Bookman’s Directory, 1900. Allen, 1900, p. 54.

- Eliot, T. S. The Letters of T. S. Eliot: Volume I, 1898-1922. Edited by Valerie Eliot and Hugh Haughton, Rev. ed. Faber and Faber, 2009.

- Field, Michael. A shorter shīrazād: 101 poems of Michael Field. Edited by Ivor C. Treby. De Blackland, 1999.

- Furst, Herbert. “The Modern Woodcut: Part II.” The Print-Collector’s Quarterly, vol. 8, 1921, pp. 267-298.

- Gould, Warwick. “Thomas Sturge Moore and W. B. Yeats: An Afterword.” Yeats Annual, vol. 4, 1986, pp. 157–160.

- Gwynn, Frederick L. Sturge Moore and the Life of Art. University of Kansas Press, 1951.

- Legge, Sylvia. Affectionate Cousins: T. Sturge Moore and Marie Appia. Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Lewis, Wyndham, The Letters of Wyndham Lewis. New Directions, 1963.

- Mukherjee, Sumita. “Thomas Sturge Moore and His Indian Friendships in London.” English Literature in Transition 1880-1920, vol. 56, no. 1, 2013, pp. 64–82.

- Pound, Ezra. “Hark to Sturge Moore.” Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, vol. 6, no. 3, 1915, 139–45.

- Powell, Grosvenor. “Pastoral Patterns in the Early Poetry of T. Sturge Moore.” English Literature in Transition 1880-1920, vol. 35, no.1, 1992, pp. 55–71.

- Tilby, Michael. “An Early English Admirer of Paul Valéry: Thomas Sturge Moore.” The Modern Language Review, vol. 84, no. 3, 1989, 565–88.

- Tonson, Jacob. “Books and Persons (An Occasional Causerie).” New Age, vol. 6, no. 18, 1910, pp. 493-94.

- Yeats, W. B. Essays and Introductions. Macmillan Papermac, 1989.

- Van Mierlo, Wim. “Reading W. B. Yeats: The Marginalia of T. Sturge Moore.” Variants: The Journal of the European Society for Textual Scholarship, vol. 2/3, 2004, pp. 135–71.

- Winters, Yvor. “The Poetry of T. Sturge Moore.” The Southern Review, vol. 2, 1966, pp. 1–16.

MLA citation:

Mierlo, Wim Van. “Thomas Sturge Moore (1870-1944)” Y90s Biographies, 2021. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021, https://1890s.ca/sturge_moore_bio/.