GENERAL INTRODUCTION

THE PAGEANT (1896-1897): An Overview

In 1895, Gleeson White (1851-98) and Charles Hazelwood Shannon (1863-1937) began preparations for the first issue of their short-lived Christmas annual, The Pageant (1896-97) for the publishing house Henry & Co. of 93 St. Martin’s Lane. As both a creative and commercial venture, The Pageant presents British aestheticism to readers as an intellectual pursuit of art history, ancient myth, modern western culture, and decadent cosmopolitanism. Its content is international and historical, mixing original poetry, drama, and short fiction by British and French authors including John Gray (1866-1934), Lionel Johnson (1867-1902), and Paul Verlaine (1844-96). Its visual art includes reproductions of influential paintings by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Gustave Moreau (1826-98), and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-82), a book illustration by Walter Crane (1845-1915), and sketched portraits by Will Rothenstein (1872-1945), and James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). With essay contributions from critics such as Alfred W. Pollard,(1859-1944) Charles Ricketts (1866-1931), and White himself, the annual constructs a narrative of British aestheticism as a collective of eclectic tastes in beauty. The Pageant serves as a space where these eclectic tastes can be placed into discourse with one another. A study of the annual as a material artifact further reveals a complex series of bibliographic design choices that mirror the diverse tastes of its editors, authors, and artists.

When White took the position of literary editor for The Pageant , he was already an influential figure in both aesthetic circles and London’s publishing industry. He served from 1893 to 1895 as the first editor of The Studio, “the wide-circulation magazine whose graphic personality dominated the fin-de-siècle art scene” (Delyfer par. 1). Art Editor Shannon, and his lover, the book and theatrical designer, Charles Ricketts, founded the Vale Press and were “at the epicentre of the movement that began with the publication of the Century Guild Hobby Horse in 1884 and ended with the closure of the Eragny Press in 1913” (Barker xxi). Through the Vale Press, Shannon and Ricketts also co-founded The Dial: An Occasional Magazine , another important periodical associated with the revival of printing (five volumes, published between 1889-1897). Shannon’s and White’s separate experiences editing aesthetic periodicals meant that they not only understood the challenges of marketing such a project, but that they also had established fruitful relationships with a number of potential contributors accustomed to the fine press printing model of the Little Magazine.

At the same time, The Pageant challenges accepted notions of the “Little Magazine.” Such periodicals sought to achieve what Koenraad Claes and Marysa Demoor call “the notion of the ‘Total Work of Art,’” in which “Bindings, fonts, lay-out, illustrations and other paratextual features all combined to achieve the ambitions of the editors who hoped that this ploy would help their publications escape the ephemeral fate of the average periodical” (134). Such a definition divides niche publications such as The Dial that sought coterie audiences for their periodicals with avant-garde content, from commercial ventures like The Strand (1891-1950), which focused on short fiction and essays that appealed to a broad audience. As both a commercial product for the Christmas market and an avant-garde contribution to British aestheticism, The Pageant, like many contemporary magazines, exemplifies a more complex notion of periodical publication, defying the “retroactive separation of elite versus popular” publications as “a naïve assumption, induced by the way literature and art histories have been written, not by the complex realities those publications reveal” (Stead 14). While not necessarily achieving the status of a Total Work of Art, The Pageant demonstrates both editors’ abilities to bring together a collective of artists, all of whom cared about the material book as an object of beauty and value. The resulting publication offered the public a Christmas annual that distinguished itself from its competitors.

For example, the reviewer for the Academy notes that the periodical is “miscellaneous enough to recall the old-fashioned Annual, an order of publication which there can be no harm in reviving” (529). Literary annuals were anachronistic by the 1890s, having come to popularity after the release of Rudolph Ackermann’s The Forget-Me-Not in 1823, themselves a revival of eighteenth-century “ladies’ pocket-books and almanacs” (Mourão 107). According to Margaret Linley, “these books went out of fashion and “by 1860, they were basically extinct, replaced by illustrated periodicals” (107). Embracing the annual’s anachronistic form, The Pageant also challenged its association, as an annual, with end-of-year assemblages released by literary and children’s magazines. The Pageant managed to stand out in the literary marketplace for its two years of publication by bringing aestheticism into the realm of the commercial gift book with the principles of the illustrated works of the late-Victorian fine presses.

In addition to its anachronistic form, another means by which The Pageant conveys its editorial vision is through its title. There are many meanings associated with the word pageant. The most appropriate meaning offered by the OED is a “tableau, representation, allegorical device . . . a public exhibition.” The Pageant exhibits a mix of contemporary and historical works; however, like most pageants, the procession is imperfect and too big to fit into a coordinated unity. The Pageant is a crown quarto bound in a claret, or dark pink cloth with gold impressing designed by Ricketts (see fig. 2). The spine provides the periodical’s name and publisher, while the front board on each volume is impressed with six flying doves carrying, not olive branches, but more elaborately leaved flowers in their beaks. The cream-coloured end papers, designed by Lucien Pissarro (1863-1944), feature a gold pattern of bonneted children marching leftward and carrying an oversized pair of pansies over their shoulders (see page banner).

Figure 1. Cover of The Pageant (1897)

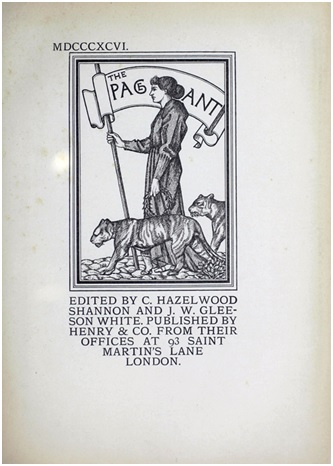

A sense of unity is carried over from the end papers to the title page for volume 1; designed by Selwyn Image (1849-1930), it is an engraving of an aesthetically dressed woman holding a banner in one hand and a laurel wreath in the other (see fig 3). On either side of her march fearsome tigers. All these figures walk in the same direction, suggesting that The Pageant may be a unified procession; however, while they march in the same direction, the pageantry is disordered. While the doves on the cover suggest peace, the figures on the title page seem to represent defiance and strength. The result is a pageant in which every one marches together but do so with a sense of individuality that defies aesthetic unity.

Figure 2. Title Page for volume one of The Pageant

The Pageant’s eclectic character is further complicated by Gleeson White’s design of an elaborately decorated red and green dust jacket for the second volume. Few examples survive today; those that do, reveal a holiday-themed aesthetic that reminds the modern reader of the volume’s commercial interest in profiting from the Christmas annual market. The implication is that the jacket and the boards appeal to different readers. While consumers might purchase the magazine for the jacket’s apparent holiday charm, they would discover underneath the aesthetic character of The Pageant’s pink-and-gold bindings. The contradictions in design speak to The Pageant as a complex commercial project. Rather than representing a disorderly failure of the Little Magazine, The Pageant actually offers an aesthetic of disorder. Its contradictions should be read as an eclectic bibliographic characteristic that reflects the difficult reality of finding even a coterie audience to buy and appreciate the diverse and dissident content of The Pageant’s literary and artistic contributions. While some elements of The Pageant may be compromises, many are well planned and part of its bibliographic and cultural significance.

For example, in both volumes, full-page plates are inserted awkwardly in the middle of stories and plays, or between poems and alongside other art works to which they hold no immediate relationship. Such placement is even more confusing because most prose essays in the volumes also include in-text illustrations. While such disorder was common among popular magazines, the well-respected firm of T. and A. Constable printed The Pageant. The firm’s then proprietor, Walter Biggar Blaikie (1847-1928) oversaw the printing of The Yellow Book and The Evergreen and was a central figure in establishing the material standards of the aesthetic movement. Moreover, White and Shannon, like editors of other aesthetic periodicals associated with the fine printing revival, chose the printing company because of their reputation for providing material quality to the books and periodicals they produced. Such disorder then, is not a symptom of poor workmanship, but a creative choice by the editors, in collaboration with Blaikie’s team. The most clear evidence to back up this claim is that the same supposed disorder continues into the second volume. The editors and printers knew what they were doing and because of that, we should consider the possibility that a sense of disorder was characteristic of British Aestheticism at the end of 1895.

Like many other avant-garde periodicals in 1895, The Pageant was prepared in the aftermath of Oscar Wilde’s 1895 trials for gross indecency (Bristow par. 17). Wilde was found guilty and served two years with hard labour for having consensual sex was adult men. Nicholas Freeman notes that the ensuing public spectacle “dominated the media” for much of the year (124). In the eyes of an “aroused society,” aesthetic artists and writers associated publicly with Wilde were tainted by what Katherine Lyon Mix calls “a hostility that did not distinguish between the guilty and the innocent,” which meant that a “number of reasonably upright individuals were unfairly condemned in this wholesale arraignment” (160). However, as Kristen Maloney, Alex Murray, and Vincent Sherry have all recently argued, interest in aesthetic and decadent art did not collapse with Wilde’s career. Numerous aesthetes remained in London to live, write, and publish. This often-underemployed community of artists provided a basis upon which The Pageant could build its own creative character. In order to survive, each periodical devised their own approach to deal with a public that now associated Wilde’s eros and aesthetic vision (as well as the desires and visions of his associates) with the medicalized view of homosexuality as pathological mental illness and the legal view of sodomy as criminal perversion. The Pageant neither hides nor exploits Wilde’s homoerotic aesthetics. Instead, it places same-sex desire and dissident gender practices into a broader historically rich discourse regarding art, beauty, and critical expression. The result is that The Pageant presents a more complex conception of art in which the queer and dissident are revealed to be central and historical elements of all Western aesthetic discourse.

Where other ornate Christmas publications cover a diverse range of topics including science, travel, history, etiquette, home décor, poetry, and children’s literature, The Pageant dedicates significant space in its pages to the themes of Aestheticism, including decadent concerns with artificiality, excess, and morbidity, and the queer erotics of sexual dissidence. At the same time, more conventional tropes of the medieval, the pastoral, and the portrait are placed side by side the annual’s more dissident works. By doing so, The Pageant gives the theme of dissent, be it social, sexual, or purely aesethetic, equal consideration alongside more mainstream concepts of art and beauty. The eclecticism of the editors’ choices require the reader of 1895 to reconsider the cultural ethics that create false divisions between artists based on an increasingly outmoded Victorian moral sense.

For example, The Pageant questions the universality of the English language by contrasting English poems by Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909) and Selwyn Image with untranslated French poems by Paul Verlaine (1844-1896) and Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949). A translation of Maeterlinck’s unsettling dramatic allegory of fate, “The Death of Tintagiles” (1, 47), shares space in the first volume with “Equal Love” (1, 189), a play by Michael Field (Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper) that disturbs the reader with themes of fillicide, gender, and power. Laurence Housman’s homoerotic male nudes in “Death and the Bather” (1, 199) stand in stark contrast to Walter Crane ’s delightful children’s illustration of sailing mice in “The Fairy Ship” (2, 229). Housman’s and Crane’s works are presented as examples of each artist’s aesthetic accomplishments and each work’s value. The beautiful work of Renaissance-era Italian and German wood engravers in the illustrations for essays by Alfred W. Pollard (1, 163) and Charles Ricketts (2, 253) offers the reader a further, historical, point of comparison and contrast to fin-de-siècle art.

Considering The Pageant’s deep interest in social and sexual dissidence, the periodical’s unfortunate marginalization of women and complete lack of representation for authors of colour mars its attempts at literary and visual diversity. Considering the prominent placement of women authors and artists in both The Yellow Book and The Evergreen, it is telling that only four works by female authors are included in The Pageant’s two volumes: Michael Field’s “Equal Love” and “Renewal” (2, 185), Margaret L. Woods’ “By the Sea” (1, 140), and Rosamund Marriott Watson’s “The Song of Songs” (2, 63). All of the visual art is from male contributors. While certainly cosmopolitan, it must be noted that The Pageant is also a patriarchal and Western European cultural document of the late-Victorian colonial empire.

Despite its limitations, by incorporating a multitude of contradictions and visions of beauty, The Pageant reflects a period of cultural uncertainty and a Decadent rejection of authority over what makes art, art. As Paul van Capelleveen observes:

Apparently it was not deemed important for this magazine to follow the new rules of book design, whereby the book was seen as a unity. The designs by Ricketts, Pissarro, and Gleeson White are quite different in character, and the whole now expresses not so much the unity of the book as the intimacy of a small coterie of artists. (par. 2)

David Peters Corbett describes the “the predominant tone” of the annual as a combination of French Symbolism and a characteristically British twist of medievalizing codswallope [i.e. nonsense]” (110). Where Capelleveen criticizes the The Pageant’s lack of unity, Corbett focusses on its failure to attract a wide audience. Corbett criticizes The Pageant , along with The Dial and The Dome (1897-1900), for failing to define “a place for art that was faithful both to the refined appreciation [their editors] understood to be its major characteristic and to the fact of its neglect and even renunciation by the public” (119). It is now an overused cliché to condemn the public for not appreciating artistic experiments, but what such criticism does not consider is that periodicals like The Pageant attempted to introduce aestheticism to a wider audience. The attempt failed. Evidence for this failure can be found in the fact that the annual ceased publication after two years. I found additional evidence in the volumes procured for this digitization project. The pages were uncut, and unread, after sitting in a library collection for a century. Not only did The Pageant fail to attract many contemporary readers, its two volumes have failed to attract critical attention ever since. Commercial success is not the only measure of success, however, and the periodical as a work of bibliographic and literary achievement should not be dismissed as nonsense because its diversity of content does not fit into an aesthetic of unity. The eclectic vision of The Pageant was an experiment in attracting audiences, and the annual’s eclectic choices are representative of the late-nineteenth century’s many experiments in literature and art influencing Pageant editors and contributors in an increasingly cosmopolitan London. Successful or not in its own time, the annual sends a message to the reader and the researcher: not all aesthetes are alike.

At six shillings, the annual was not only beautiful but also an affordable gift book for the middle-class shopper. The Dial was ten shillings whenever released, The Yellow Book and The Evergreen were each five shillings per volume (four times a year for the former, and semi-annually for the latter), and The Savoy cost two shillings and six pence on a quarterly and then monthly basis. Released before Christmas, The Pageant asked consumers to see it as an affordable source of pleasure. As the advertisement for the second volume in the Pall Mall Gazette proclaimed: “GIFT BOOKS for one’s self and others” (Advertisements & Notices, 3). The ad placement for the 1897 volume in the December 18, 1896 issue of the Pall Mall Gazette appeared immediately following another from Sampson, Low, Marston and Company for that company’s latest 6- shilling and 5-shilling novels. Competitively priced, The Pageant’s cost aligns it with the new market for single-volume novels popular with both publishers and authors seeking to avoid the interference of the circulating libraries (Altick 112-117).

Charles Ricketts receives no credit as an editor, but he was heavily involved in the preparation of The Pageant. Ricketts’s involvement makes sense, considering Nicholas Frankel’s assertion that he “introduced French symbolist art and ideas into Britain,” and “almost single-handedly invented the figure of the modern typographer or graphic designer” (3). The Ricketts and Shannon Papers held at the British Library illustrate the arduous process of production faced by The Pageant’s editors despite their previous experience in periodical publication. For example, in a letter to Michael Field, Shannon laments that “ The Pageant is more troublesome in temper than The Dial (It is supposed to have a public).” While filled with content similar in scope and concern to The Dial , The Pageant was a commercial endeavor meant not only to sell as a profitable periodical itself, but also to promote the various literary works brought out by its publisher. Henry & Co. used the advertisements at the end of The Pageant to promote the novels of Yellow Book contributor, John Oliver Hobbes (1867-1906) (Pearl Craggie) and Alexander Tille’s planned English translation of Friedrich Nietzsche’s complete works in eleven volumes.

Much like The Pageant’s contents, its advertisements have little consistency. The first volume only promotes its own publisher’s list and provides advertising space for the Swan Electric Company. However, the second, and final, issue includes space for the publisher’s lists for Marcus Ward & Co., and Hacon and Ricketts at the Sign of The Dial. The reason for the change remains unknown but suggests that Henry & Co. needed the support of other publishers and hoped to continue the periodical’s run by charging fees for advertising space. Giving Ricketts space to advertise the works of his own publishing house would also serve to appease art editor Shannon. The changing practices suggest a publishing company learning how to appeal to both commercial and aesthetic audiences and how to secure a profitable position within the publishing industry. However, as Laural Brake (2001) argues in relation to The Savoy, “the belief in the compatibility of a popular audience and high quality was misplaced” (174). While the initial success of periodicals like The Yellow Book and The Savoy suggest that such ventures can be profitable, widespread and long-term commercial success were elusive. There is little scholarship on H. Henry and Company. The Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism (2009) only provides information available from a physical examination of the periodical. Koenraad Claes’s biography of the publisher for The Yellow Nineties Online is the most detailed study to date. Claes warns that because of “a lack of preserved ledgers or other substantial archives, scholars might never be able to acquire much more definite information about Henry & Co.’s proprietors” (par. 10). More discernible is that The Pageant’s eclectic physical and aesthetic character, while certainly a consequence of market uncertainty, demonstrates the flexibility of its contributing aesthetes to adapt to commercial demands.

While White had experience with such expectations previously as editor of The Studio, The Pageant was the first publication that Shannon and Ricketts edited that demanded commercial success. While there are no surviving accounting records for The Pageant , Ricketts’s and Shannon’s correspondence sheds light on the situation. In another letter to Michael Field, Shannon and Ricketts complain of their taxing efforts as they prepare the second volume for the printers: “it has been out of hand for some weeks and like last year we are not on speaking terms with Messrs. Henry.” The letter suggests that they did not feel in control of The Pageant’s production. The Pageant was officially a collaboration between Shannon, White, and the Messrs. Henry, but that collaboration is not always apparent when reading Ricketts’s and Shannon’s letters, none of which are addressed to these professional associates. Despite their frustrations, and perhaps because of their taxing efforts, the two volumes produced represent a unique contribution to aestheticism’s periodical history with an eclectic character all its own.

While the Pageant only produced two annual volumes, it managed to elicit positive attention from contemporary book reviewers and art critics. The Pall Mall Gazette published an apparent interview with White that poses as a critical review. The reviewer tells White that he had heard it was “to be a sort of Yellow Book.” “Not in the very least,” White responds, claiming, “If anything, it recalls the scope and purpose of the Germ,” and arguing that he is “perfectly certain that no such illustrations have ever been seen in English work of this kind before” (1895, 3). Crediting the Swan Electric Engraving Company for the quality of the image reproductions, the interviewer-author allows White to assure readers that

There is nothing whatever meretricious, or French, or problematic, or improper in The Pageant. It is a serious artistic conception, and to artists, in the first place, it will appeal. So far as the public are concerned, it is a long way the best thing of the kind that has ever been offered to them, and the price is ridiculously small. (1895, 3)

The reviewer for The Sketch interviewed Shannon, who insisted that he was “allowed a free hand” in selecting the art contents, emphasizing that The Pageant’s “predominant Pre-Raphaelite spirit” was his “ideal” – an ideal that moves the reviewer to urge readers to “Take up and admire” the volume.

The Academy insisted that The Pageant is “a remarkable gift-book,” despite being “a little too much with the spirit of Pre-Raphaelite art” (529). In The Commonwealth , “M.D.” proclaimed that

A distinctly new note in the world of art and letters has been struck this Christmas. Superficially, we might say, we are in a period of transition from the sickly productions of the art of the Decadent to the really beautiful work represented by the leaders of the Birmingham School. The Pageant supplies a definite contradiction to this, and is the best example of this distinctly new spirit. (39)

The most critical review came from The Morning Post where the reviewer was uncomfortable with The Pageant’s “strange combination of the new with the old.” The critic concluded by pointing out the periodical’s “inappropriate interleaving of the plates with the letterpress [as] one of the discordant elements that help to make ‘The Pageant’ remarkable” (3). On October 17, 1896, The Academy (No. 1276) announced that a “somewhat improved and enlarged” volume of The Pageant would be published that Christmas season (forward dated to 1897 just as volume 1 was dated for 1896 while published at the end of 1895) (290). The Spectator praised the second volume as “a book put together with so much taste in the choice of its contents, the arrangement of its type, and the design of the cover” (274). While the contributors remained open to criticism, reviewers seemed pleased to recommend The Pageant to readers as a valuable and collectable aesthetic artifact.

With the distinct character of an art journal, The Pageant offers an argument for aestheticism’s enduring cultural relevance beyond the yellow nineties. It demonstrates how Aestheticism is a continuation of a historical art project that began with the Renaissance. In its open conversation between 1890s aestheticism and the early modern artists who inspired their work, The Pageant recalls Walter Pater’s related concept of the Renaissance. Rather than reading it as a time period, Pater saw the Renaissance as a “many-sided movement,” with “a much wider scope then was intended by those who originally used it to denote that revival of classical antiquity in the fifteenth century which was only one of many results of a general excitement and enlightening of the human mind” (xxii). The Pageant’s presentation of aestheticism becomes a fin-de-siècle iteration of Pater’s Renaissance: “an outbreak of the human spirit” that he traced well before the 15th century across Europe into the late-nineteenth century within the experiments of aestheticism and decadence (xxii). Neither censoring its provocative imagery, as seen in the post-Beardsley Yellow Book, nor exploiting it in order to provoke controversy, as seen in Leonard Smithers’s The Savoy, The Pageant draws on Aestheticism’s middle-class roots and engages with contemporary Victorian culture through critical conversations about history and myth. The Pageant narrates the connection between the present and the past in a manner that asks readers to revise their preconceptions of Aestheticism beyond its immediate connection to the scandalous 1890s.

For example, throughout both volumes are mythical and biblical references. These references defy historical and cultural boundaries, confusing time, place, and order. Rossetti’s “The Magdalene at the House of Simon the Pharisee” seems to depict fifteenth-century Florence rather than the world of Jesus over fourteen-hundred years earlier. Ricketts’s “Psyche in the House” presents the ancient Greek myth from Apuleius’s The Golden Ass as if Cupid, upon his rescue of Psyche, set up her up in an urban home of fin-de-siècle Europe. Botticelli’s “Pallas and the Centaur” (1482), vaguely references myths of Athena, sometimes known by the epithet Pallas, the goddess of arts, crafts, and war (Tripp 116, 442). She grips the hair of a centaur, a figure of unchecked sexual desire. Not only does the painting reference Greek myth and an erotic subject, it is also an example of Renaissance art. Its content suggests a mythic place for Sandro Botticelli in Aestheticism’s presentation of art history. It also suggests that the concept of eros is important to aestheticism’s reading of western art history. These works also suggest that the stories of the ancient Greeks and ancient Christians that define Western cultural history are living aspects of the cultural present. Fin-de-siècle aestheticism is presented as a means by which we can access these long-standing aesthetic discourses. Myth takes the reader out of time by suggesting the timeless. By turning to these tropes, The Pageant presents itself as a gateway to a supposedly timeless discourse of aesthetics and eros.

Mythic claims to historically sanctioned relevance may sound like so much wishful thinking, but The Pageant asks the reader to reconsider aestheticism, not as a marginal peculiarity in the study of art and literature, but as an important development in the study of beauty from an anachronistic “universal formula” into a modern and distinctly subjective discourse (Pater xix). With its eclectic mix of historical precedent and contemporary innovation, The Pageant is an important example of Aestheticism’s continued relevance in periodical culture in the 1890s. These two volumes reconsider the movement’s multitude of voices and their complicated role within late-Victorian cosmopolitan culture and the commerce of print culture.

A Note on the Text Used in the Yellow Nineties Edition

The digital edition of The Pageant is based on material copies held in the editor’s private library. As ex-library copies deacquisitioned by Huron College Library in London, Ontario, the two volumes show significant wear with stamps, small tears, and foxing. During research for this project, the editor compared his copies to those held in the British Library and discovered that damage to his personal copies was not uncommon. The British Library copies had been poorly rebound, causing irreparable destruction to the original bindings. Instead of seeking out another Pageant in mint-condition, the editor asks readers to consider the role of the archive in preserving historical periodicals. The choices made by British Library archivists altered the material presentation of The Pageant and completely erased Pissarro’s contributions to the binding (replacing his end papers with card stock). This resulted in copies that showed little evidence of careful preservation. The British Library’s conservation processes did not prevent damage to the volumes. The editor purchased the volumes uncut and undertook the cutting process for the purposes of studying and digitizing the contents. The traditional archive, often argued to be superior to digital preservation, neither protected these volumes, nor exposed them to new readers. Digitization has preserved the damage to both volumes, showing readers the physical result of The Pageant’s neglect in archival preservation as well as literary scholarship. In addition to offering more widespread access to The Pageant, the editor’s other goal with this digital edition is to bring attention to the limits of traditional book preservation and the need for libraries to change the way that books are catalogued and preserved for future readers as historical documents.

© 2018 Frederick D. King, Dalhousie University

Works Cited

- “Advertisements & Notices.” Pall Mall Gazette, 18 Dec. 1896. British Library Newspapers, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/60nRr9. Accessed Jul. 30 2018.

- Altick, Richard D. The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800-1900 . 2nd ed., with foreword by Jonathan Rose, Ohio State UP, 1998.

- “A Pageant and How It Was Made.” Pall Mall Gazette, 6 Nov. 1895. British Library Newspapers, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6onFN5. Accessed Jul. 30 2018.

- Barker, Nicholas. Foreword. The Vale Press: Charles Ricketts, a Publisher in Earnest by Maureen Watry. Oak Knoll Press and The British Library, 2004, pp. xxi-xxii.

- Brake, Laurel. Print in Transition, 1850-1910: Studies in Media and Book History. Palgrave, 2001.

- Brake, Laurel and Marysa Demoor, editors. Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism in Great Britain and Ireland. The Academia Press and The British Library, 2009.

- Bristow, Joseph. “Oscar Wilde (1854-1900).” Y90s Biographies , edited by Dennis Denisoff, 2010. Yellow Nineties 2.0 , edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. http://1890s.ca/wilde_bio.html. Accessed May 15, 2018.

- Capelleveen, Paul van. “A Paper Wrapper for a Pageant.” Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, Wed. January 16, 2013. http://charlesricketts.blogspot.ca/2013/01/77-paper-wrapper-for-pageant.html. Accessed May 15, 2018.

- Claes, Koenraad. “Henry & Co. (1889-97).” Y90s Biographies , edited by Dennis Denisoff. The Yellow Nineties 2.0 , edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/henryco_bio/

- Claes, Koenraad and Marysa Demoor. “The Little Magazine in the 1890s: towards a ‘Total Work of Art,” English Studies, vol. 91, no. 2, 2010, pp. 133-149.

- Corbett, David Peters. “Symbolism in British ‘Little Magazines’: The Dial (1889-7), The Pageant (1896-7), and The Dome (1897-1900).” The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines. Vol. I, Britain and Ireland 1880-1955. Oxford UP, 2009, pp. 101-119.

- Delyfer, Catherine. “Gleeson Joseph William White (1851-1895).” Y90s Biographies, edited by Denis Denisoff, 2013. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/gleeson_bio.html

- Dowling, Linda. “Letterpress and Picture in the Literary Periodicals of the 1890s.” The Yearbook of English Studies, vol. 16, Literary Periodicals Special Number, 1896, pp. 117-131.

- Frankel, Nicholas. “Charles de Sousy Ricketts (1866-1931).” Y90s Biographies, edited by Dennis Denisoff, 2010. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. http://1890s.ca/ricketts_bio.html

- Freeman, Nicholas. 1895: Drama, Disaster, and Disgrace in Late Victorian Britain. Edinburgh UP, 2014.

- Linley, Margaret. “The Early Victorian Annual (1822-1857).” Victorian Review, vol. 35, no. 1, 2009, pp. 13-19.

- “M.D.” “Christmas Books and Pictures,” The Commonwealth , vol. 1, no. 1, 1896, pp. 39-40. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, http://tinyul.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5BMBa0.

- Mahoney, Kristin. Literature and the Politics of Post-Victorian Decadence. Cambridge UP, 2015.

- Maurão, Manuela. “Remembrance of Things Past: Literary Annuals’ Self-Historicization.” Victorian Poetry, vol. 50, no. 1, 2012, pp. 107-123.

- Mix, Katherine Lyon. A Study in Yellow: The Yellow Book and Its Contributors. Greenwood Press Publishers, 1969.

- Murray, Alex. Landscapes of Decadence: Literature and Place at the Fin de Siècle. Cambridge UP, 2017.

- “Pageant (Book Review).” The Academy, Oct. 17, 1896, vol. 50, no. 1274, p. 290. Periodicals Archive Online. http://ezproxy.library.dal.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1298641169?accountid=10406. Accessed Jul. 30, 2018.

- Pater, Walter. The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry. The 1893 Text , edited by Donald L. Hill, U of California P, 1980.

- Potolsky, Matthew. The Decadent Republic of Letters: Taste, Politics, and Cosmopolitanism from Baudelaire to Beardsley. U of Pennsylvania P, 2013.

- Ricketts, Charles. “A Note on Original Wood-Engraving (illustrated).” The Pageant, vol. 2, 1896, pp. 253-266.

- Ricketts, Charles, and Charles Shannon. Letters 26 and 63, Ricketts & Shannon Papers. Add MS 58085-58118, 61713-61724. The British Library, London.

- Sherry, Vincent. Modernism and the Reinvention of Decadence. Cambridge UP, 2015.

- Stead, Evanghelia. “Reconsidering ‘Little’ versus ‘Big’ Periodicals.” Journal of European Periodical Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2016, pp. 1-17. https://ojs_ugent.be/jeps/article/view/3860

- “‘The Pageant,’ and Two Other Miscellanies (Book Review).” The Spectator, Feb. 22, 1896, 0. 274. Periodical Archives Online . http://ezproxy.library.dal.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1295381538?accountid=10406. Accessed Jul. 30, 2018.

MLA citation:

King, Frederick D. “ The Pageant (1896-1897): An Overview,” Pageant Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0 , edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/pageant_overview/